Just Like Poetry, Fashion Is a Language of Emotion: Q&A with Amir Al Kasm

Interview by NOUR DAHER

Syrian fashion designer Amir Al Kasm reflects on memory, loss, and the emotional landscapes that shape his work. Moving between Syria and Lebanon, craft and poetry, silence and expression, Amir speaks about fashion as a language, one that holds emotion and resilience.

Nour Daher: Can you tell us a bit about where you grew up; where you live now; and how you began this journey in fashion?

Amir Al Kasm: I’m from Talkalakh, Syria, and I moved to Lebanon during the Syrian war in 2011 as a refugee. I was 11 years old at the time. Fashion has been a part of me long before I realized it. As a child, whenever my mom bought heels, I would try them on and walk around the house. At 16, I discovered Creative Space Beirut, a free fashion school in Lebanon that opened the door for me to enter the world of design. I later worked at Krikor Jabotian as a pattern maker to financially support my own brand. In 2023, I won Fashion Trust Arabia in the Evening Wear category, which became a major milestone in my journey. Today, I’m building my brand while teaching at Creative Space Beirut. To teach there is deeply meaningful to me, because seeing young talents reminds me of my own early days as a student.

ND: How did this win change things for you?

AQ: It was a really important moment for me, both personally and professionally. Before that, I didn’t have much support. I was working to financially sustain myself and to keep creating. Winning FTA gave me the push and recognition I needed. It opened beautiful opportunities, like having my garments displayed at Harrods in the UK, showcasing with Maison Pyramide in Paris, and presenting my Mylaya dress at M7 in Qatar for the celebration of seven years of FTA. It was a turning point that reminded me why I never stopped believing in what I do.

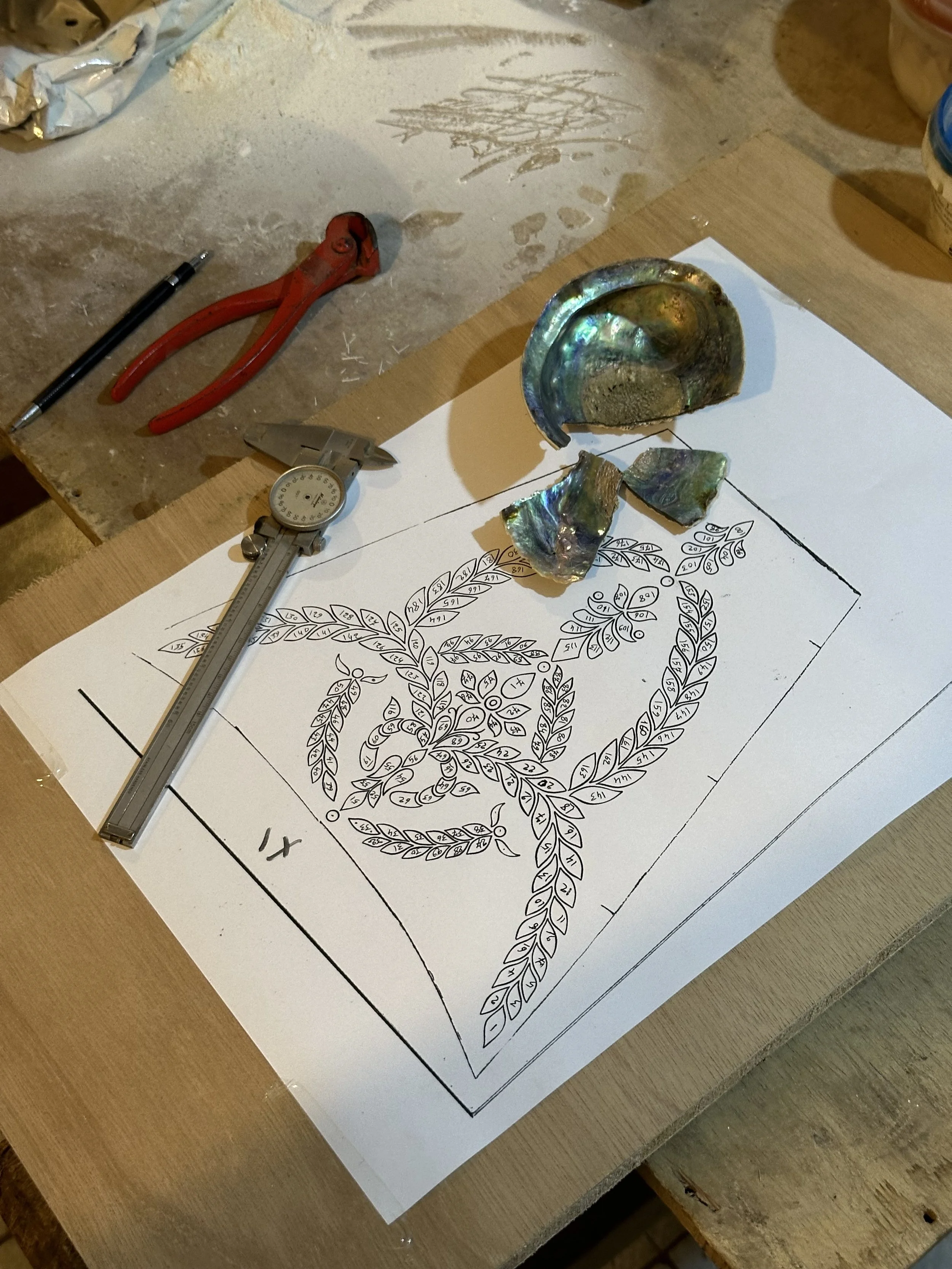

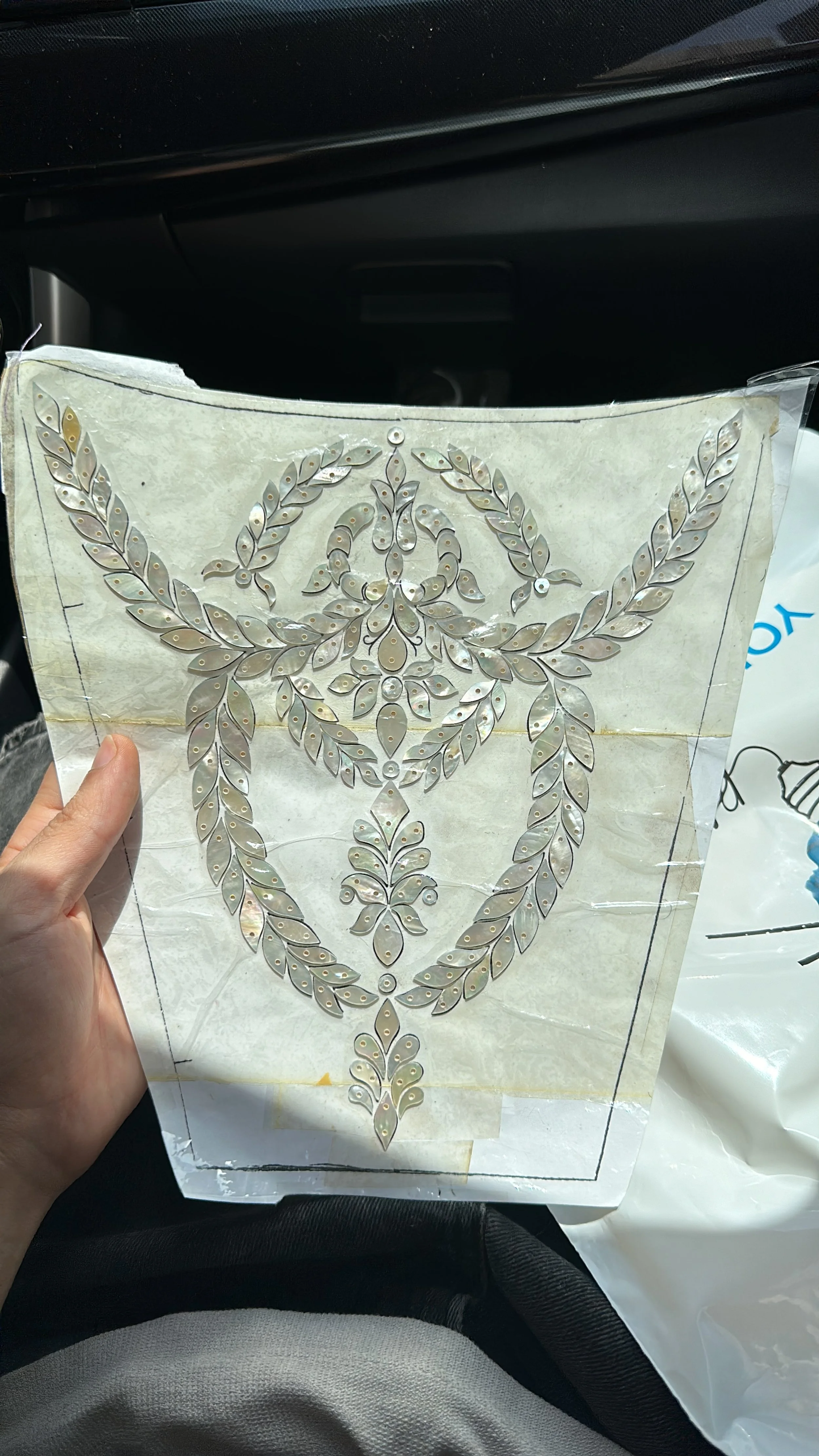

ND: A key element of your collection is the Damascene mother-of-pearl inlay. What’s it like working with a furniture artisan for fashion?

AQ: Damascene furniture crafting is a very meaningful part of this collection. My dream was to make these pieces in Damascus, but the situation didn’t allow it. By chance, I discovered a Lebanese artisan exhibiting at Sursock Palace. He was an older master with decades of experience. When I showed him my sketches inspired by Damascene furniture, he lit up. He had always wondered how this craft could live in fashion. We met many times, and I visited his workshop often. He showed me pieces he had collected from Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Germany, and France — each country with its own signature patterns and motifs. Seeing those old pieces opened a new world for me. The collaboration became a dialogue between heritage and movement, between the stillness of furniture and the life of fabric — creating something soft, emotional, and wearable.

ND: How do you see Syrian crafts, which carry a long history, evolving in today’s fashion landscape?

AQ: I think Syrian crafts have so much potential to evolve within fashion. They hold centuries of skill and emotion. Seeing these traditional techniques find new life through unexpected collaborations and personal storytelling is what excites me most. A lot of the tailors working in Lebanon are actually Syrian. You can really see the talent in their hands: there’s a deep sensitivity, patience, and precision that comes from years of inherited craftsmanship. I believe our crafts should and can exist beyond nostalgia — they can be modern, bold, and part of global conversations while still keeping their soul. For me, it’s about honoring those hands and that heritage, and assisting them to continue to grow, adapt, and inspire future generations.

ND: Your collections carry an emotional depth. Can you share more about that?

AQ: There’s always a hidden story in my work — something that I feel deeply and live long with, but not always name. Not everything needs to be explained; some emotions resist clarity, and I’ve learned to trust fabric, shape, and the smallest details to carry what words cannot.

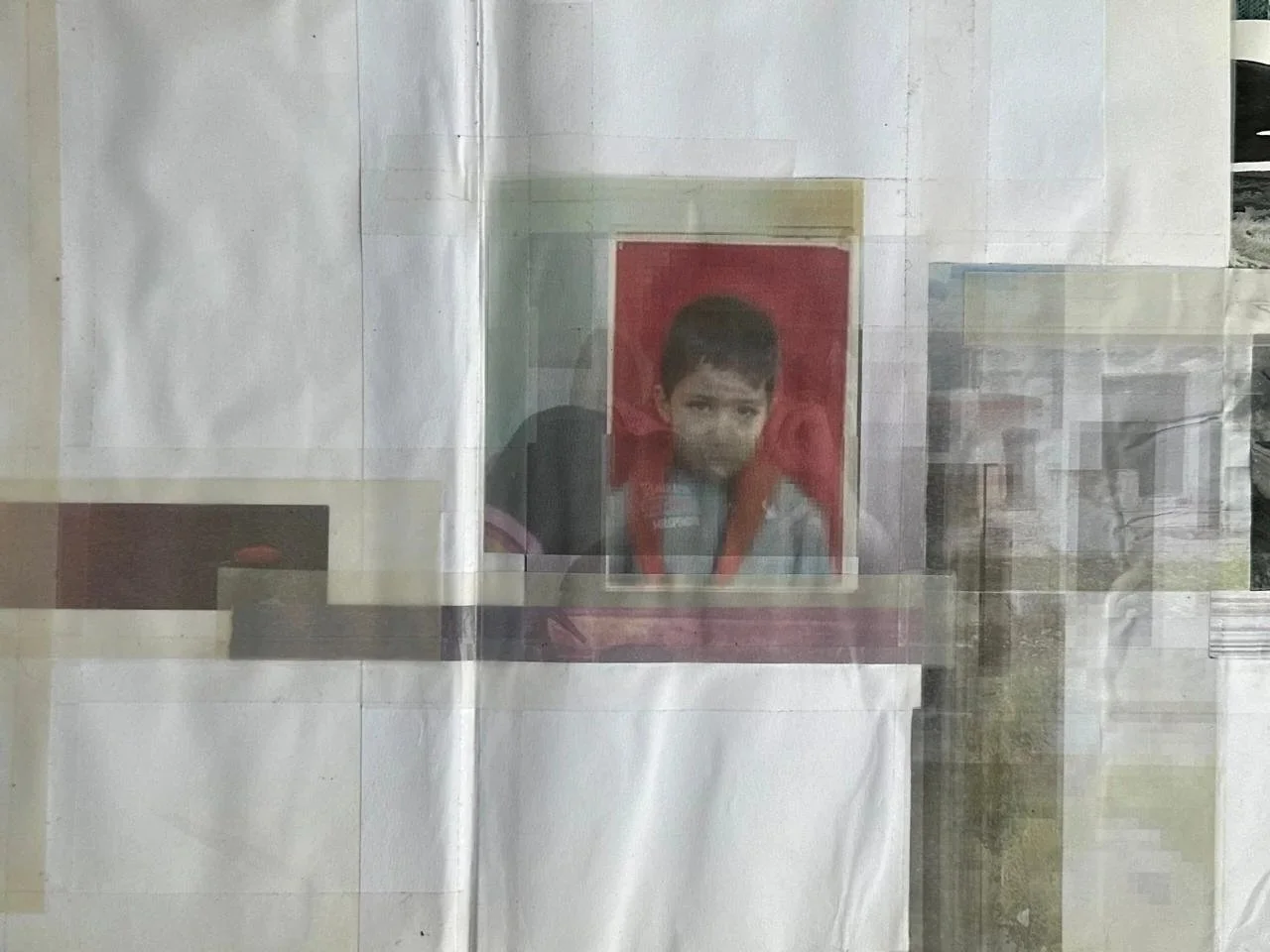

The loss of my brother lives quietly inside my practice. For many years, it was marked by uncertainty rather than closure. He was imprisoned in Sednaya, and for a long time, we did not know his fate — was he alive or gone? That suspended state, the not-knowing, shaped the way I worked and felt. My graduation collection grew out of a single family photograph: an image that appeared perfect from a distance, but dissolved into pixels the closer you looked. That slow breaking apart mirrored what my family was living through: how something once whole can fragment without warning — how clarity and comfort can disappear.

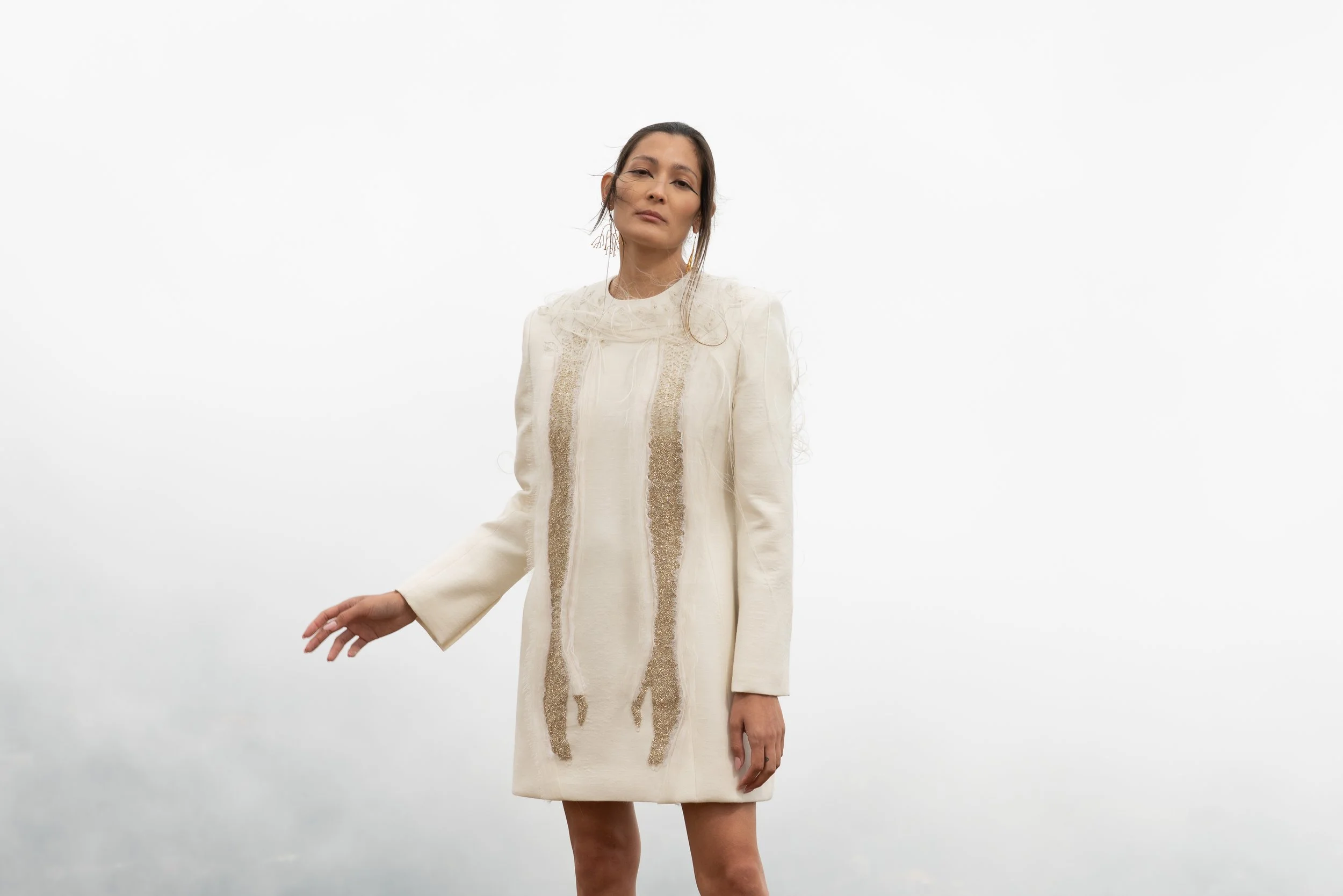

After that came Fallen Angel, a white collection photographed in the mountains. It was an attempt to imagine peace for my brother, or at least to search for it, even though I couldn’t fully reach it myself. Unresolved emotion entered the work through contrast: the emergence of red, the violence of the prints, and the image of birds devouring a single bird at the center. It reflected how the world felt then — chaotic, consuming itself, offering no simple resolution.

We learned recently that we lost my brother right before the fall of the regime in Syria. This knowledge, painful as it is, brought an end to 14 years of suffering and uncertainty. My latest collection comes from a softer place, not because the grief has disappeared, but because I am learning to live alongside it, to breathe despite it, and to let go of the weight of not knowing. Believing that he has left a world marked by violence for a more peaceful place to rest has allowed a different kind of emotion to enter my work. It feels like a quiet release that comes only after enduring so much pain.

ND: After 14 years away, you returned to Syria. How did that journey transform this collection?

AQ: Returning to Syria was a surreal experience. It felt like a dream; I never imagined going back, especially that for so long, Syria only existed in my mind as a place I couldn’t return to. Being there brought back all the memories of my childhood, my family, and especially my brother. That visit awakened so many emotions, and I tried to translate them into this collection. I had already started working on it by the time I visited, but being there reconnected me with why I create; it became less about the technical process and more about expressing what I truly felt.

ND: Nizar Qabbani appears as a recurring presence in your work. How does poetry enter your creative world?

AQ: It plays a big role in my process. Qabbani became part of my world during my FTA collection, Min Bilad El Yasamine. I was researching him deeply, and his words began to guide my emotions. He writes about everything: Damascus, women, love, longing, politics, heartbreak… His poetry holds contradictions that I also feel inside me and often try to express through fabric and form. With each collection, he appears differently. Sometimes it’s a specific poem; sometimes it’s just the feeling of his writing. I keep his portrait near me as I work: it grounds me. Just like poetry, fashion is a language of emotion. When words touch me deeply, I translate them into movement and texture.

ND: Your journey spans Syria, Lebanon, and the communities that shaped you. How do these places influence the way you create?

AQ: I always say I carry Syria in my blood and Lebanon in my heart. Being Syrian today, in Lebanon, the region, and beyond, comes with both a profound cultural identity and real obstacles that are hard to navigate. Living in Lebanon became a big part of my story. Lebanon cared for me; it’s where I grew, learned, and started building my path as a creative. Even with all the challenges, this country gave me the space to become who I am. Both Syria and Lebanon shaped me deeply and taught me empathy and how to turn emotion into creation.

I’ve been lucky to be surrounded by people who believed in me, especially here in Lebanon. Creative Space Beirut was and still is one of the most important places in my life. It shaped me not just as a designer, but as a person. The support I found from the people there gave me the strength and confidence to keep going. Even the moments of doubt became part of my growth. Both the supportive and the difficult sides taught me resilience and reminded me that creation can be protected through connection and care.