Fashion Influences in Family Archives: From Syria, Yemen, Zanzibar & Egypt

Words by Roba Khorshid

What started as mere curiosity about my father’s ancestors, somehow led to a months-long personal research project that inadvertently turned me into the family’s historian. As a child, I would hear names of people and faraway places, but couldn’t quite figure out how I was connected to these people and places. It wasn’t until I grew older that I realized that modern borders and travel restrictions weren’t always the norm. The migrations and cultural exchanges between countries, especially in the late 1800s and the first half of the 1900s, have very much shaped the fabric of our family—figuratively and literally. The following photos and accompanying narratives explore family, history, and fashion.

Sayyida Sekina

A few years ago, I stumbled upon a treasure trove of family photos digitized by my father’s late cousin. Amongst the hundreds of photos, I found this one of my paternal great-grandmother that no one in my direct family had seen before. This is the earliest photo we have of her, which makes it very special. Her name was Sekina Abdul Rahman Gamali سكينة عبد الرحمن جمالي and she was about 20 years old in this photo, which was taken in Cairo, Egypt on November 13, 1918 by S. Mitry and S. Andonian Studio.

Sekina is dressed in an Ottoman-influenced style typical of urban Egyptian ladies. The most noticeable part of this outfit is her yashmak يشمك, a transparent white face veil made of fine muslin or silk chiffon. Rather than covering her face, it’s hanging on one side with the end tucked into her skirt. Her large black scarf is tied in the back, with some of her hair visible. She is wearing an outer skirt of embroidered black silk or satin with a scalloped hem over a dress. Her collar, ankle-length skirt, silk stockings, and heels were all signs of European influence on clothing.

At first, it was the clothing that caught my attention, but then the date on the photo got me more curious to learn about her journey to Egypt. Her father, originally from Aleppo, was a merchant who had settled in Zanzibar with his wife, a Yemeni poet from Al-Hudaydah. They had four children who were all born and raised in Zanzibar. My great-grandmother, the youngest child, was married at a very young age to the 8th Sultan of Zanzibar, Sayyid Ali Bin Hamoud. As the wife of the Sultan, she was known as Sayyida سيدة Sekina, an Arabic title which means “noble woman”.

In 1915, a few years after her husband was forced to abdicate by the British, she moved to Egypt along with her mother and her husband’s two boys from a previous marriage. Her brother had already been sent to the Saidieh Secondary School in Giza, and she had a few Egyptian/Syrian/Turkish cousins living there. She first settled in the Sakakini district and later moved to Heliopolis.

The plan was for her to reunite with her husband in Cairo, but he was not successful in obtaining permission to travel. She was widowed a month after this photo was taken when he passed away in exile in Paris after catching the Spanish flu. Years later, she married my great-grandfather, an Egyptian from Minya in Upper Egypt. She passed away in 1990 when I was six.

I’ve managed to piece Sekina’s story together by speaking with my father and his cousins, but there are so many unanswered questions about her life that I would have loved to ask her. For example, I’m also really curious about how she dressed before moving to Egypt. I assume that she dressed in the Ottoman-style rather than the style of Omani women in Zanzibar, because of her Syrian origins and her father’s trade with Istanbul.

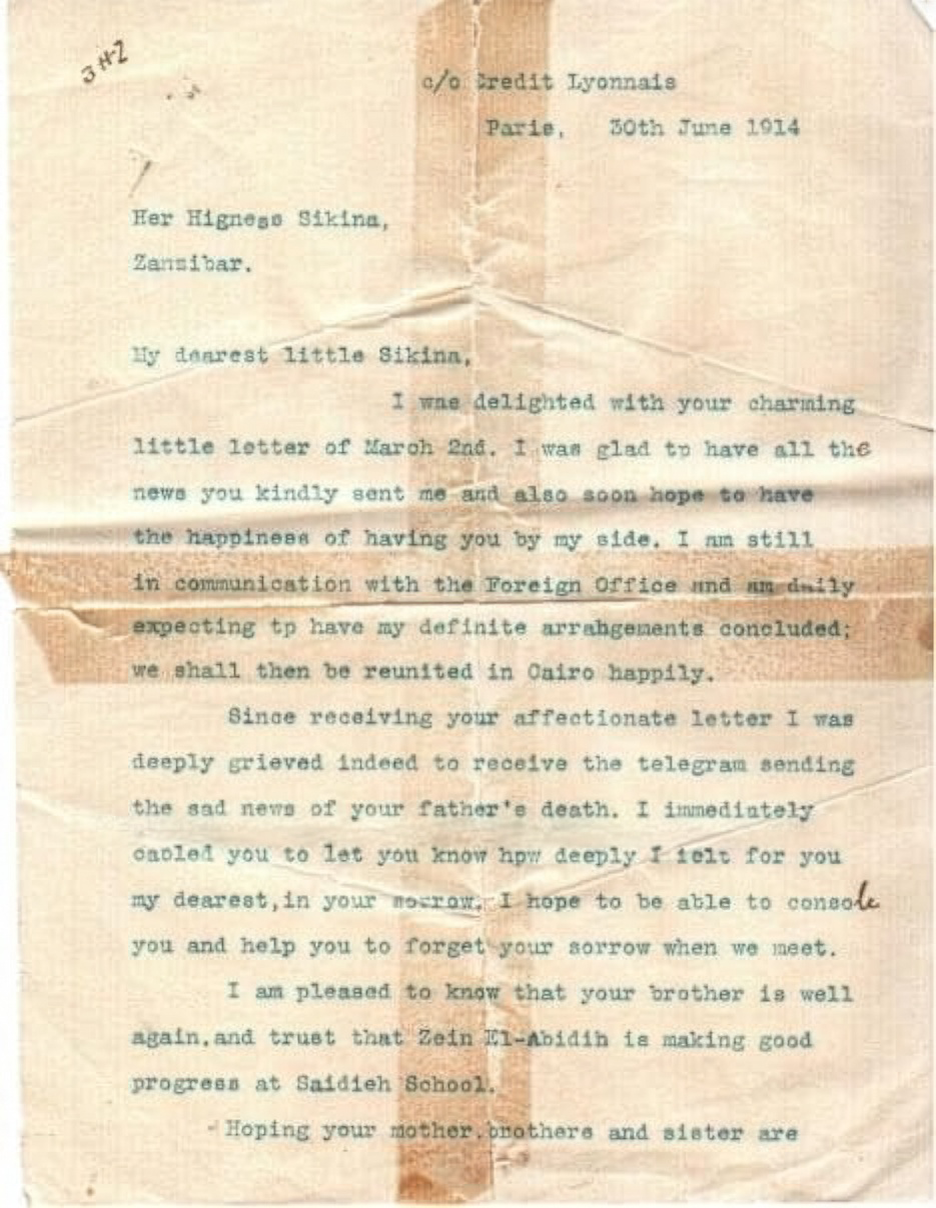

A letter dated June 30th, 1914 sent to my great-grandmother Sekina from her first husband while he was in exile in Paris

A signed photo that her first husband sent her while he was in exile in Paris around the mid-1910s

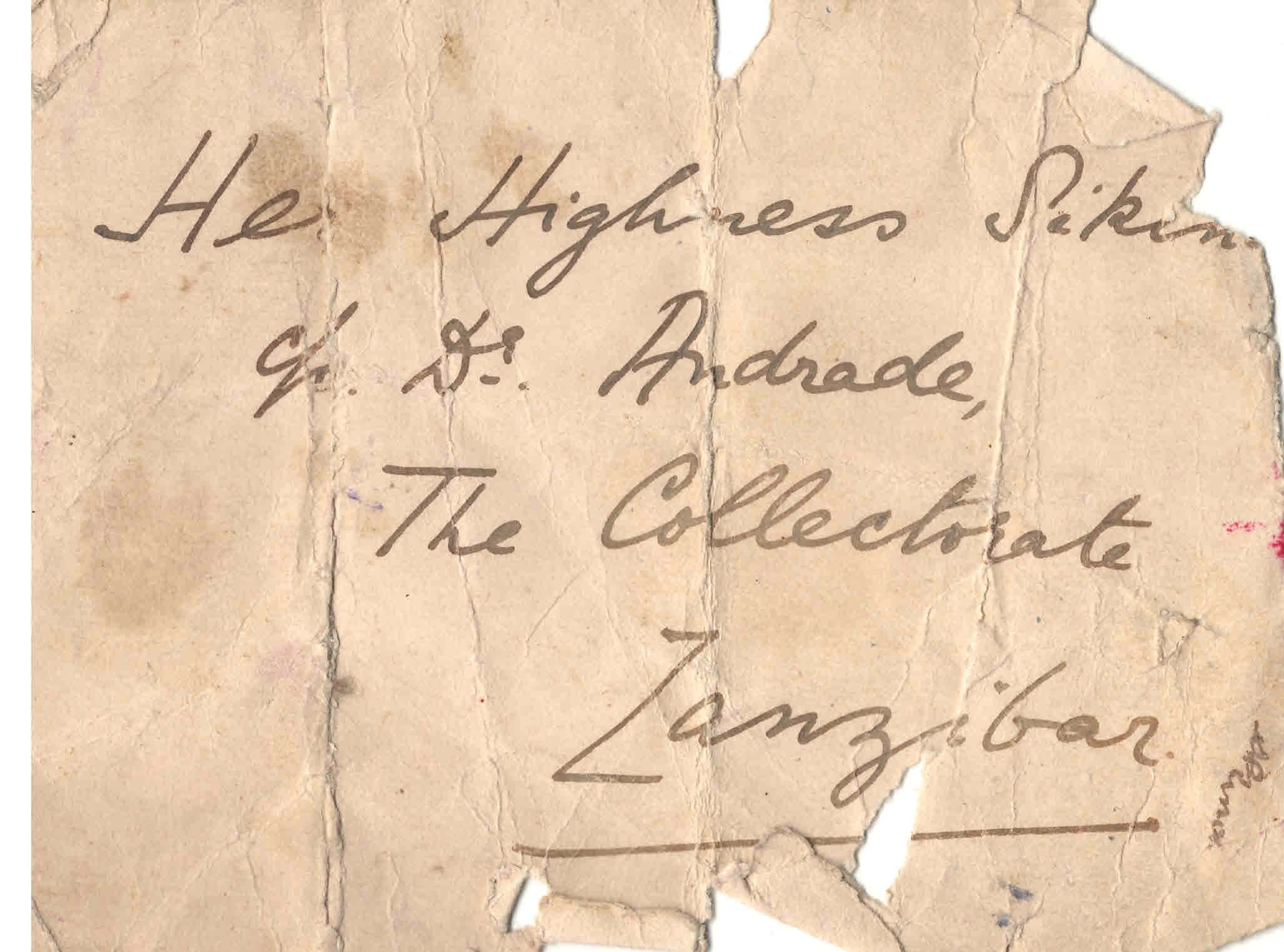

The envelope in which the 1914 letter was enclosed

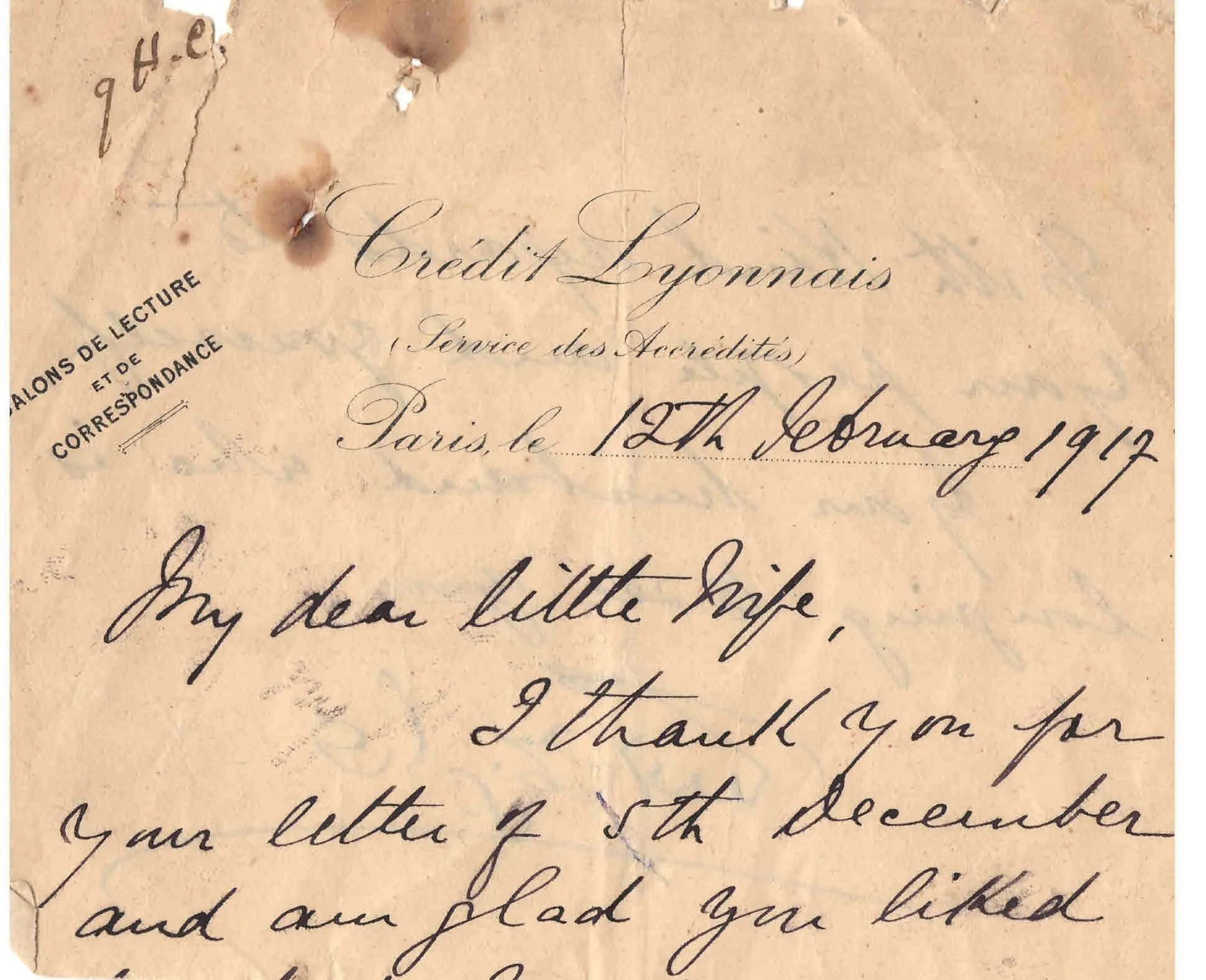

Part of a letter her first husband sent her on February 12, 1917, from Paris to Cairo, where she had moved. He passed away on December 20, 1918, at the age of 34

Sitt Umm Al-Khair

My great-grandmother, Umm Al-Khair bint Khidr أم الخير بنت خضر, photographed in Cairo, Egypt, on May 14, 1922 (photographer unknown). She was known as Sitt ست Umm Al-Khair, which literally means “lady” in Arabic.

Like her daughter, she too adopted the style of urban Egyptian ladies when she settled in Cairo. Her black scarf (tarha طرحة) is worn in the more traditional way, tucked behind the ears, with the rest of the scarf serving as a cape (younger women tied their scarves in the back, keeping up with 1920s fashion). Her yashmak يشمك (white face veil) can be seen hanging down one side of her face and tucked under the scarf, exposing her face for the photo. She is wearing a collared white blouse buttoned up to the top, an outer skirt of black satin fastened on one side using a neat row of black buttons, and black heels.

Her father was a Yemeni trader from the Mnibari منيبارى family of the Red Sea port city Al-Hudaydah. Her mother was half Somali and half Indian. According to her great-niece, she lived in Aden near the historic Al-Aydarus mosque. Her family then moved to Zanzibar, where she met and married my great-grandfather, who was her father’s friend and possibly business partner. She lived there until she moved to Egypt with my great-grandmother Sekina in 1915, a year after Umm Al-Khair’s husband passed away.

She was a poet and valued education. She had previously traveled to Egypt earlier in the 1910s, accompanying her older daughter Fatma, and her younger son, Zein El-Abedeen, to enroll them in schools in Cairo (French and English, respectively). It is said that she used to host women’s literary salons in her home in Cairo, but unfortunately don’t have any of her poetry saved. The only thing we have left of her belongings is a very interesting book of prayers that had been passed on to her by her Yemeni family.

Sheikh Gamali

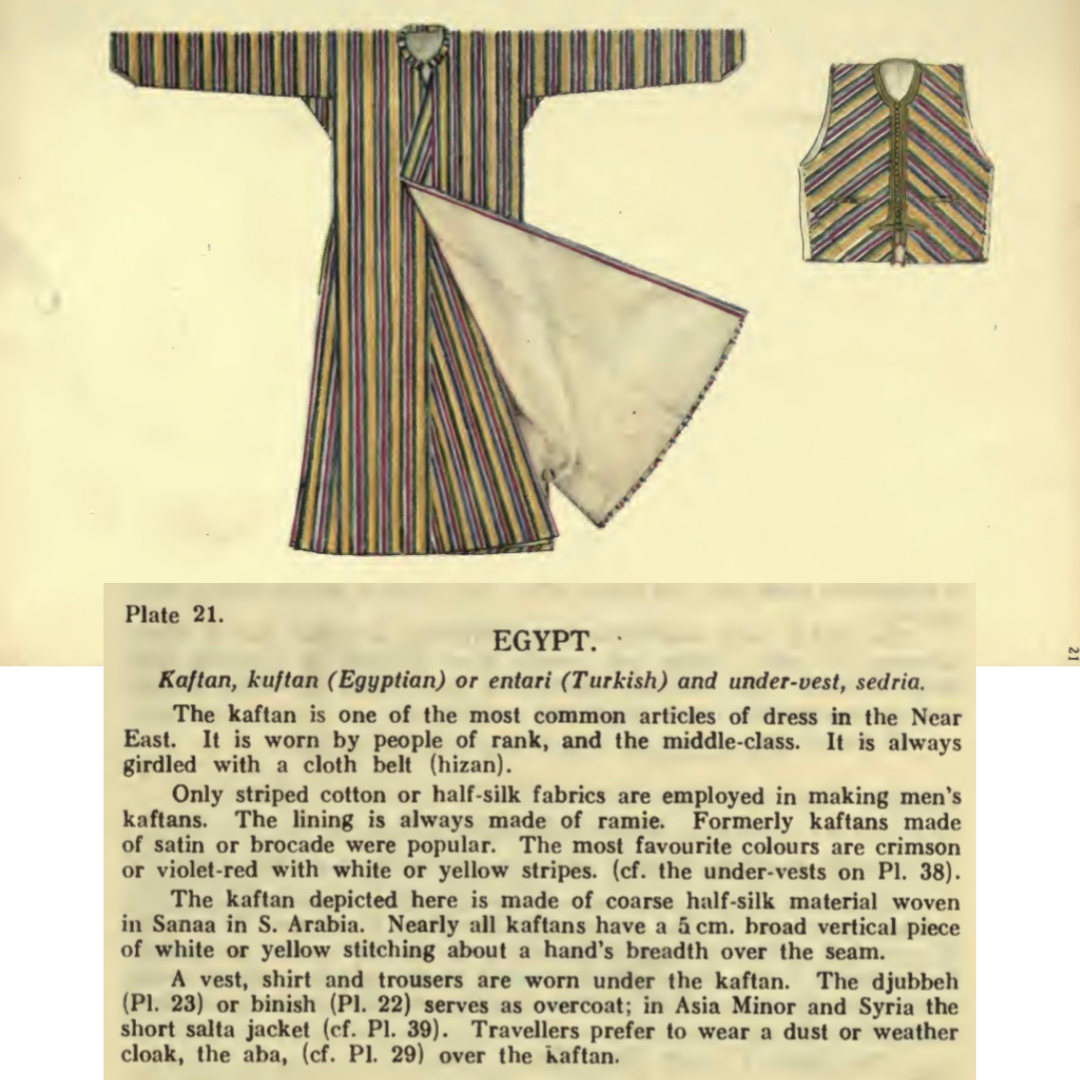

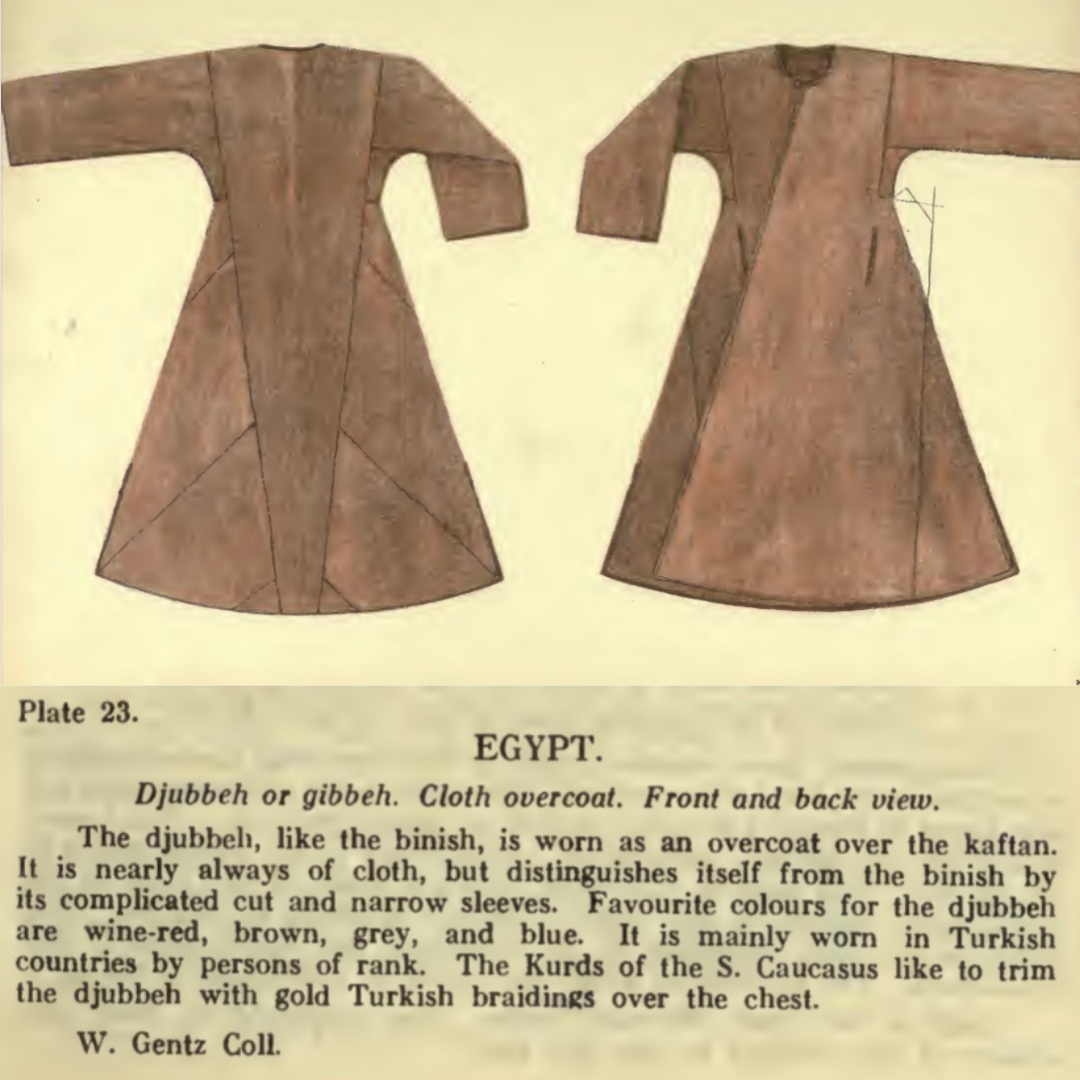

From Max Tilke’s book Oriental Costumes: Their Designs and Colors (1922)

My great-grandfather, Abdul Rahman Mohamad Gamali عبد الرحمن محمد جمالي, photographed in Zanzibar in the early 1900s. This is the only photo we have of him, and I’ve always been fascinated by it. Photographer unknown.

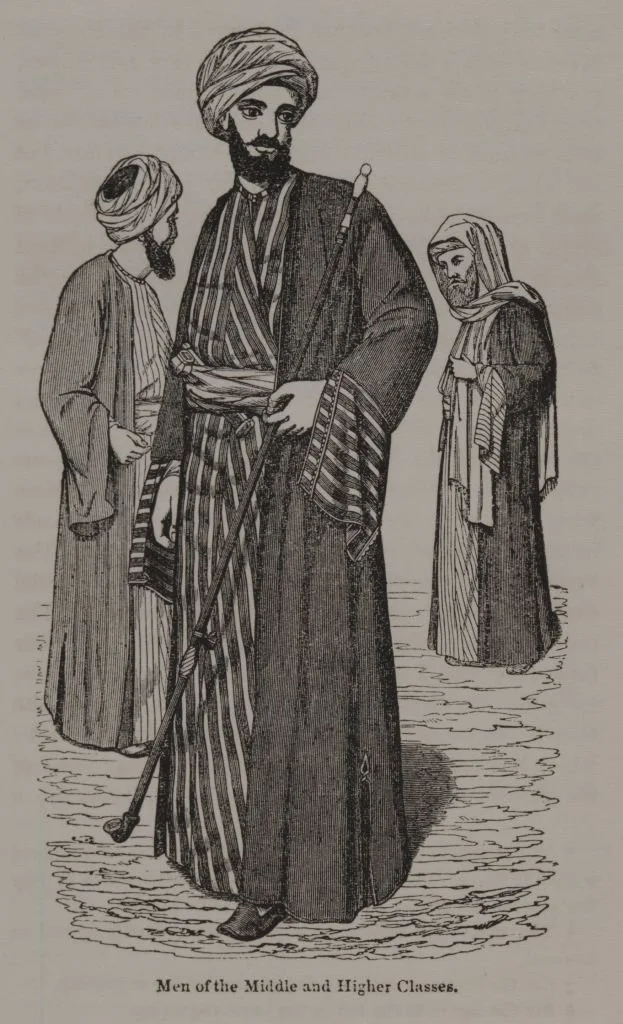

He is dressed in a striped kuftan قفطان (kaftan), a hizam حزام (belt) consisting of a patterned shawl wrapped around his waist, and a jubbah جبة or gibbah (a long overcoat). His ‘imma عمة (turban) consists of a patterned, or perhaps embroidered, shawl wrapped around a tarboosh (felt cap). His round-toed leather shoes were most probably slip-ons.

Originally from Aleppo, Abdul Rahman was a merchant who lived in Stone Town, Zanzibar, and owned a plantation in Matetema. He was known in Zanzibar as Sheikh Abdul Rahman Turki because he traded with Istanbul. He had family in Istanbul, Aleppo, and Cairo (family name spelled Cemali, Jamali, and Gamali, respectively). Judging by the Syrian mother-of-pearl inlay furniture, this photo was taken in his home or office rather than a studio.

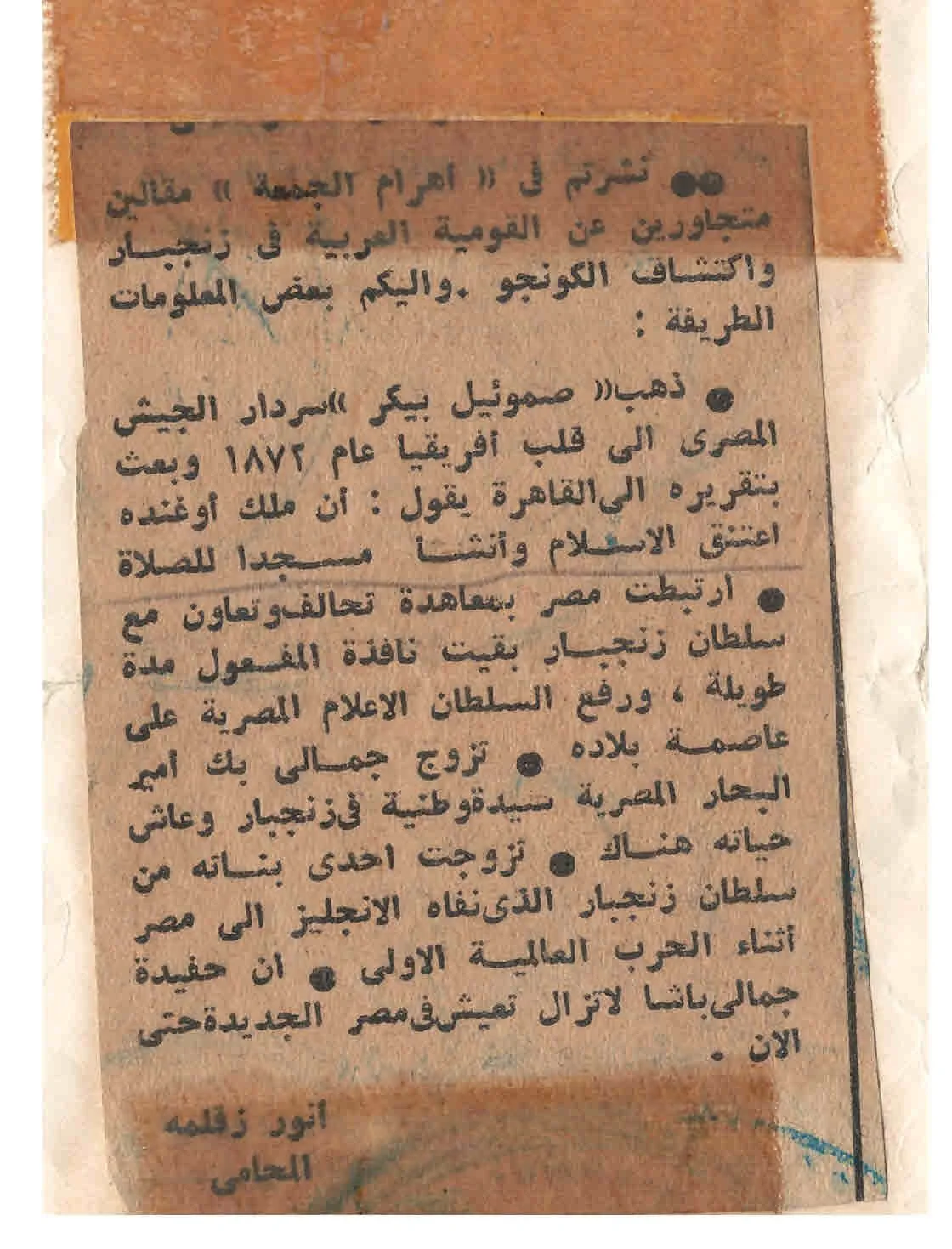

He passed away in 1914 and was buried in Zanzibar. It is still a mystery why he lived in Zanzibar, but an Al Ahram newspaper clipping that my father found in my grandmother’s belongings has given me a clue. It referenced an admiral named Gamali Bey whose daughter married the Sultan of Zanzibar. After further investigation, I learned that Egypt’s ruler, Khedive Ismail, had sent a fleet from Suez in 1870 under the command of Mohamad Gamali Bey to explore the East African coast along the Red Sea. While I have no proof yet, this admiral was quite possibly Abdul Rahman’s father, which could explain the Zanzibar connection.

Author: Anwar Zaklama. Date unknown. Al-Ahram newspaper clipping referencing my great-grandfather, the admiral Gamali Bey, who lived in Zanzibar and whose daughter married the Sultan of Zanzibar. The clipping also references my grandmother, who still lived in Heliopolis during the time this was written. My father found this clipping in his mother’s things

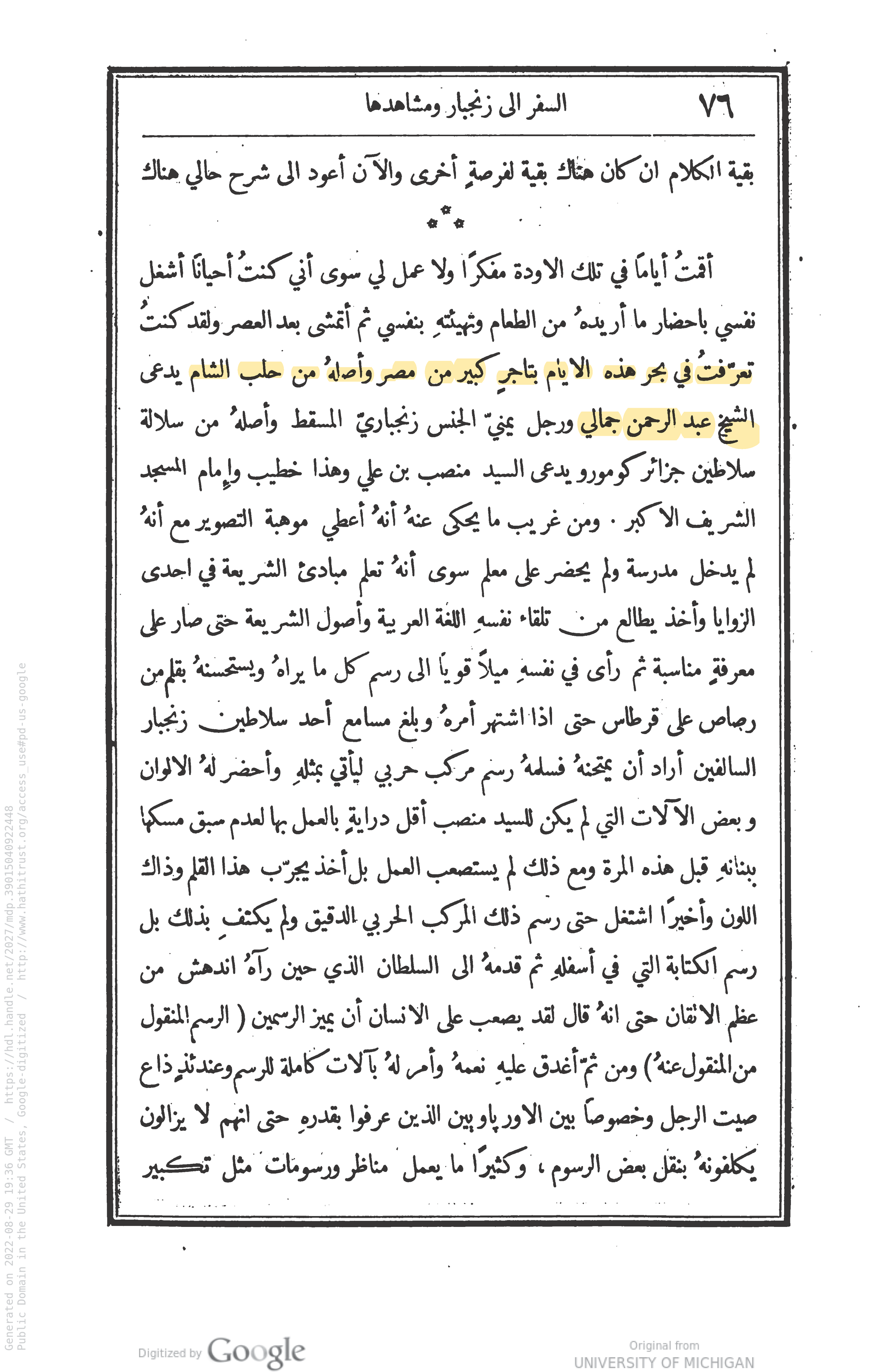

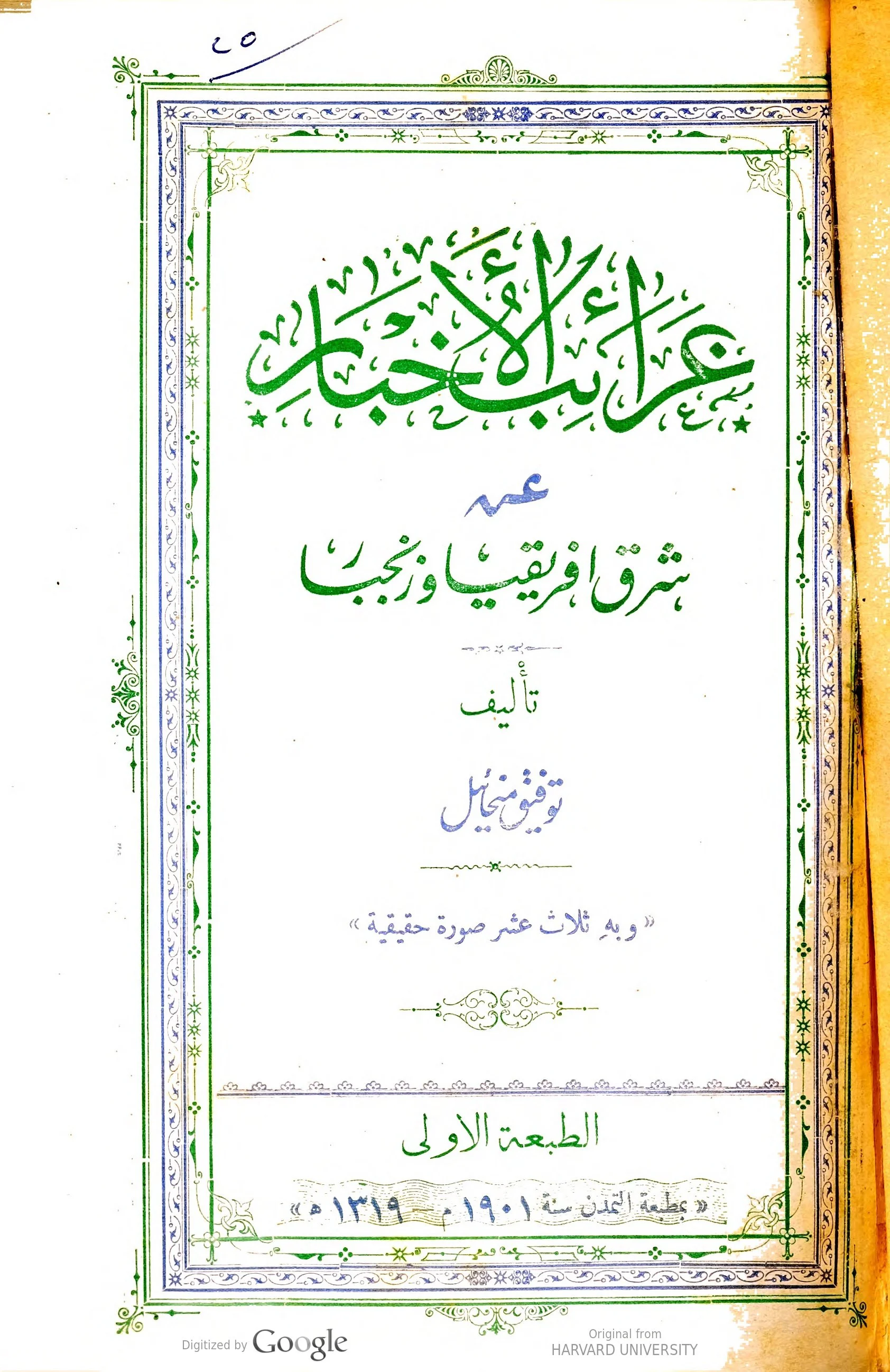

Digital book in the public domain. Found on Hathi Trust. P.76 of the book titled غرائب الأخبار عن شرق أفريقيا وزنجبار “Gharāʾib al-akhbār ʻan Sharq Ifrīqiyā wa-Zanjibār” published in 1901, where the author توفيق ميخائيل (Tawfik Mikhail), an Egyptian Copt, mentions befriending my great-great-grandfather Abdul Rahman Gamali. He refers to him as an important trader/merchant from Egypt who was originally from Aleppo, Syria.

I found a reference to my great-grandfather in Zanzibar in this book on page 76: Gharāʾib al-akhbār ʻan Sharq Ifrīqiyā wa-Zanjibār, Mīkhāʼīl, Tawfīq / al-Ṭabʻah 1. / [Cairo]: Maṭbaʻat al-Tamaddun, 1901 (public domain)

Garment Photos: From Max Tilke’s book Oriental Costumes: Their Designs and Colors

Men of the middle and higher classes: Edward Lane’s illustration of middle- and upper-class Egyptian fashions. 1836. CC BY-SA 2.5

Settling in Cairo

Luckily, my great-grandmother Sekina was fond of getting photographed, so we have many photos of her and her family in Cairo. Like other urban Egyptian women of her generation, she adopted European-style clothing with the advent of the Egyptian feminist movement in the 1920s. Ottoman-style clothing and face veils gradually went out of fashion, and European-style clothing began to be worn in public. The latest fashion, particularly French-style, was readily available at the many department stores in Cairo and Alexandria, and also sewn by seamstresses for those who could not afford ready-to-wear prices.

After her first husband passed away in exile in 1918, she never returned to her birthplace, Zanzibar. Eventually, she and her two brothers had a large social circle of relatives and friends in Cairo (the only sibling who stayed in Zanzibar was their older sister). Their Heliopolis home was frequently visited by Zanzibari Omanis who had relocated to Cairo from Zanzibar, those who were studying in Egyptian schools and universities, and those who were just visiting the country. My great-grandmother and her brothers, and eventually my grandmother and her brother, were also guardians to many Zanzibari Omani relatives studying at boarding schools in Cairo and Alexandria.

To this day, whenever I mention our family’s connection to Zanzibar, many Zanzibari Omanis (even those not related to our family) tell me that they or their parents had visited my great-grandmother’s Heliopolis home, a tradition that continued with my grandmother and now with my father.

Photos of Sekina Gamali in the 1920s and 1930s taken by Studio Photo London in Heliopolis, Cairo (founded by Armenian photographer

K. Berberian).

Maintaining Swahili

Despite moving to Cairo in her late teens, my great-grandmother was most comfortable with Swahili, the language of her childhood, but also spoke Arabic and English. Swahili was the language she used the most with her children. My late grandmother spoke it with my father, and it was also their secret language around us kids. Even though I never learned the language, I was usually able to decipher what the conversation was about using my limited vocabulary.

Photographer unknown. My great-grandmother was photographed in 1930 on a picnic to Fayoum Oasis with her two children, Samira (my grandmother) and Sameeh, from her second marriage to an Egyptian.

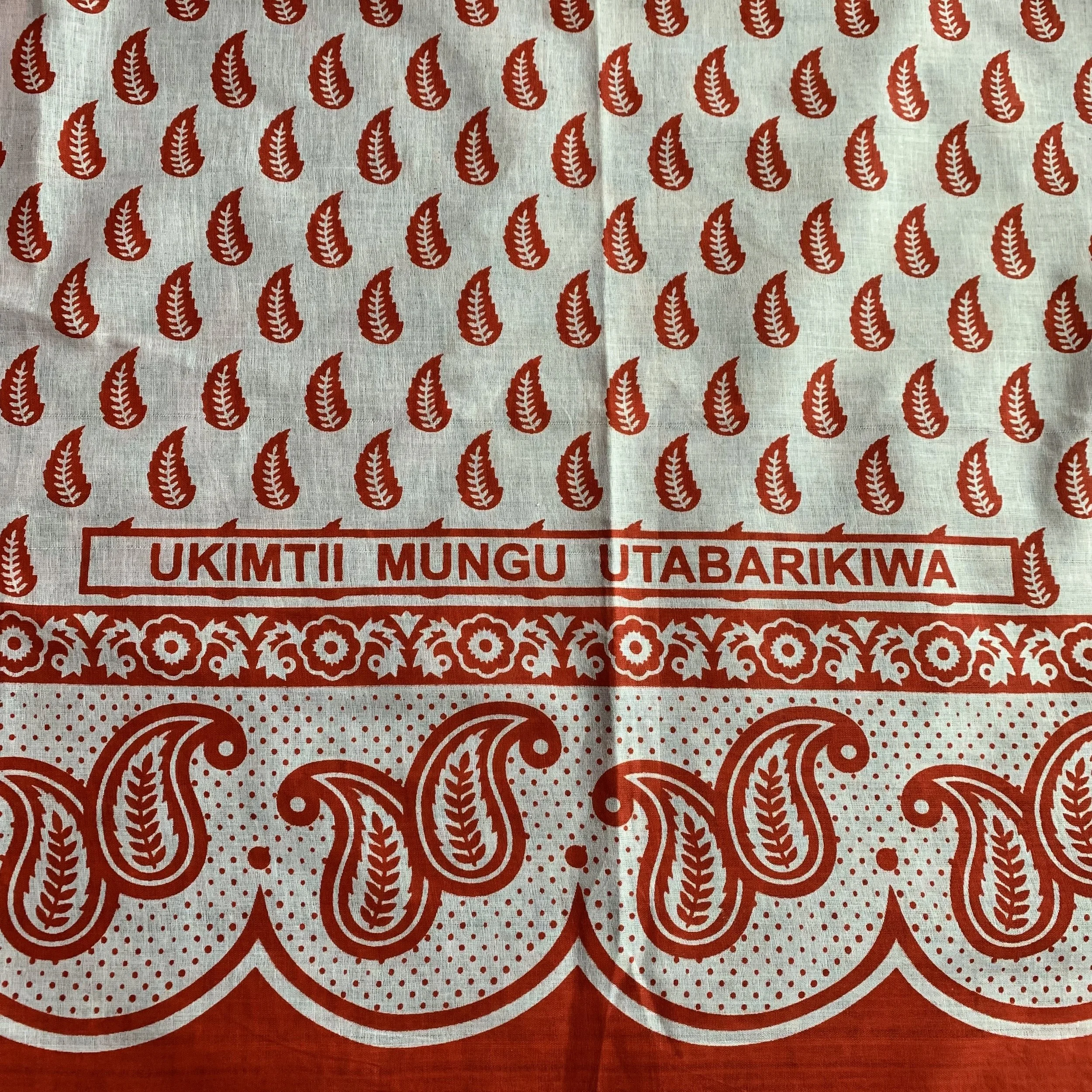

As a child, I remember asking my grandmother to translate the Swahili sayings on the edges of her kangas, the East African rectangular cotton cloths known for their patterns and bright colors. First produced in the mid-1800s, kangas are worn along the coast of East Africa, particularly Kenya, Tanzania, and the island of Zanzibar. Omani women also wear them because of the historical connection with Zanzibar. They are sold in a pair meant to be worn together as a set and either simply wrapped or sewn into different styles. Swahili sayings weren’t added to kangas until the early 1900s. Kangas were mainly designed and printed in India and exported to East Africa and Oman. In the 1950s, they started being produced in East Africa as well.

Kangas were a staple in her home as well as ours, used for a variety of purposes. We used them as prayer clothes, beach coverups, lightweight kids blankets, furniture covers, and also used the worn-out kanga to wrap our clothes before storing them at the end of a season. Our Zanzibari Omani relatives often gifted us kangas when they visited, and we amassed quite a collection over the years. I recall a particularly beautiful hot pink floral kanga that I turned into a beach skirt in my teens.

My sister and I were in the late 1980s at our grandmother’s home with a kanga by our feet

A kanga, which was recently gifted to my sister. The Swahili saying printed on the edge is “Ukimtii mungu utabarikiwa,” which translates to “If you obey God, you will be blessed.”

Kangas were a staple in her home as well as ours, used for a variety of purposes. We used them as prayer clothes, beach coverups, lightweight kids blankets, furniture covers, and also used the worn-out kanga to wrap our clothes before storing them at the end of a season. Our Zanzibari Omani relatives often gifted us kangas when they visited, and we amassed quite a collection over the years. I recall a particularly beautiful hot pink floral kanga that I turned into a beach skirt in my teens. One day, I hope to travel to Zanzibar with my father to visit my great-grandfather’s grave and possibly uncover more of the family story.

About the Author

Roba Khorshid is a Boston-based Egyptian fashion designer, embroidery artist, and fashion history enthusiast. She was born in Muscat, Oman, and grew up in both Muscat and Cairo, Egypt, where she often accompanied her mother on visits to the traditional fabric and jewelry souqs. She learned to sew as a child and loves collecting traditional fabrics and embroidered dresses from around the world. The history of fashion fascinates her, and she is passionate about researching her cultural heritage. She loves learning about how the clothes we wear relate to the social, political, and art movements of the time. She completed a Fashion Design Certificate from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in 2019.