Reticular Chemistry, Reticulated Lives:Omar M. Yaghi’s Nobel and the Politics of Representation

Words by Safaa Elidrissi Moubtassim

“I wrote exactly the kinds of stories I was reading: All my characters were white and blue-eyed, they played in the snow, they ate apples, and they talked a lot about the weather, how lovely it was that the sun had come out.”

Representation isn’t charity; it’s the infrastructure for belonging. We, as members of marginalized communities, often struggle to see ourselves reflected in the stories that define our heritage and the systems that shape our societies, which weaken our sense of connection and identity and limit our potential. Similar to the classic "doll test" with young children that showed a strong preference for white dolls over Black ones, demonstrating the early influence on self-worth and aspirations, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie warned about “the danger of a single story," sharing her personal experience.

On the Relevance of Representation: Why Seeing Ourselves Matters

In science, the narratives we've been fed have largely focused on a limited group of protagonists. Our collective imagination has been firmly conditioned to picture Nobel Prize winners, and by extension, scientists, as white men in their sixties or seventies. That’s why it matters to discuss the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, awarded to Omar M. Yaghi, a Jordan-born scientist of Palestinian origin who later became a Saudi citizen, and whose work founded reticular chemistry and transformed materials science.

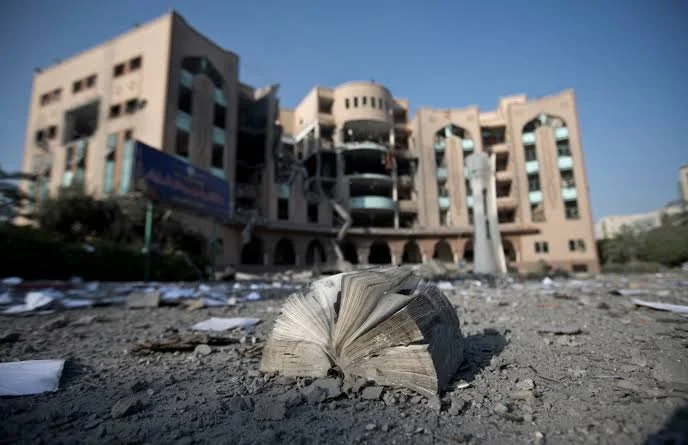

As we tell Yaghi’s story of success, we must also confront the heartbreaking reality of what is being erased. Since October 2023, Gaza’s universities have been deliberately targeted and bombed, campuses destroyed, and countless professors and students killed. This devastating loss of higher education has been aptly termed “scholasticide” by observers. How many Omar Yaghis, full of potential and hope, have we lost in those lecture halls and labs turned to rubble? How many stories of shattered dreams and lost futures remain untold?

Arab Science and the “Golden Age” Myth

Popular histories still rehearse an Orientalist script: a medieval “Golden Age,” a precipitous fall, and a modern Arab world bereft of science, even though historians have been dismantling that story for decades. George Saliba’s work, for instance, shows continuity and originality well into the early-modern period, and critiques the teleological rise-and-fall narrative that flatters Europe while flattening everyone else. (see Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance)

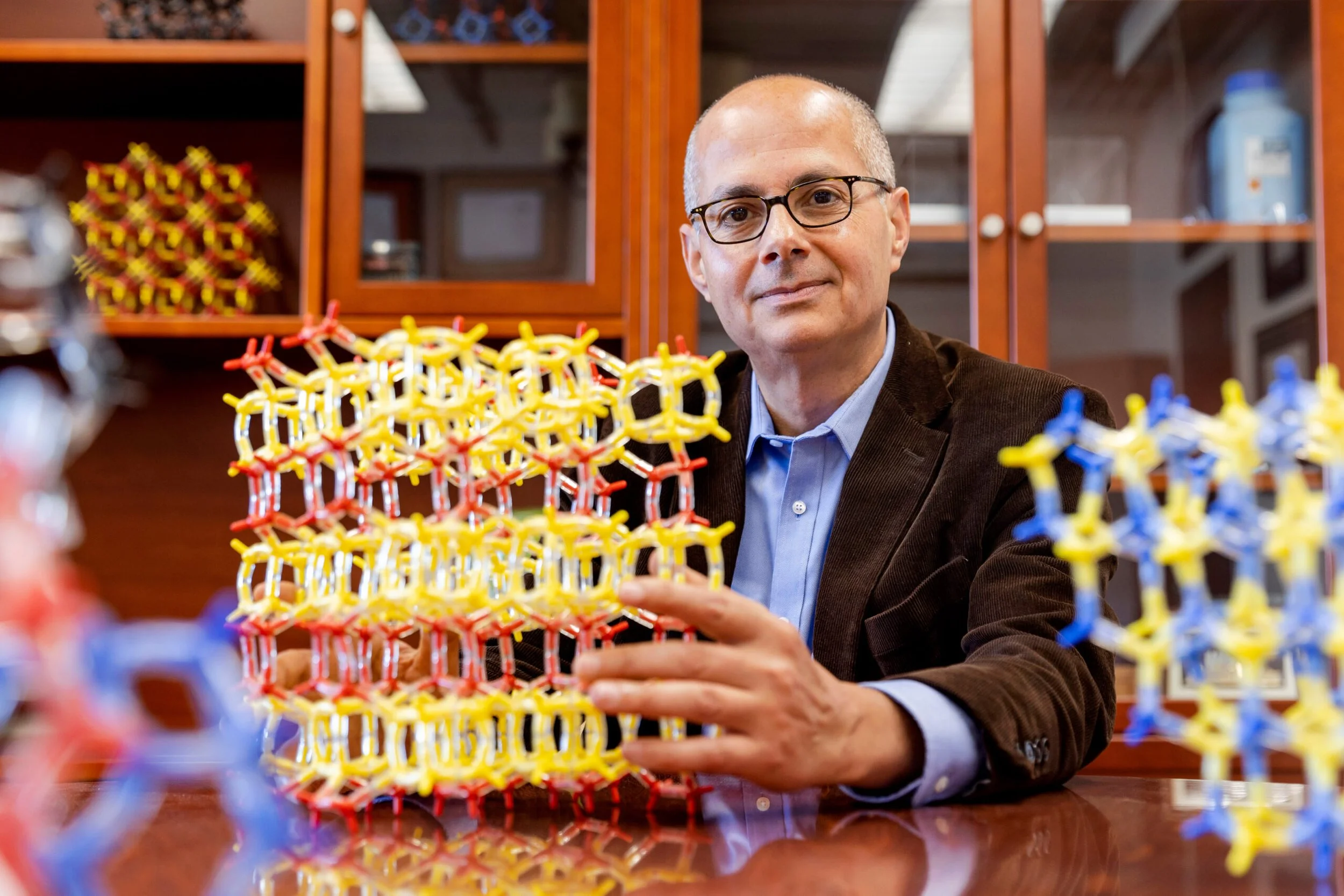

Omar M. Yaghi’s career is a contemporary rebuttal to that absence trope. His field-making contributions created what he calls reticular chemistry: stitching molecules together into crystalline frameworks with consistent pores and predictable functions. In the mid-to-late 1990s, chemists could make delicate metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), but they tended to collapse as soon as solvents were removed. The landmark paper “Design and synthesis of an exceptionally stable and highly porous metal-organic framework” (Nature, 1999) changed that: by organizing metal clusters and organic linkers into stable secondary building units, Yaghi and colleagues created a framework that remained porous even after drying, resulting in permanent pores. Imagine a molecular sponge whose holes are engineered at the scale of a nanometre (10-9 m). Because those holes are regular and vast (in internal surface area), you can soak up specific gases, sort molecules by size, or anchor catalysts in the pores. The Nobel committee’s 2025 description captures it simply: crystals with large internal cavities through which gases and chemicals can pass.

Yaghi then expanded the concept beyond metals. In 2005, his team reported covalent organic frameworks (COFs): all-organic porous crystals. If MOFs are like frameworks built with metal hubs and organic supports, COFs are the all-carbon (and boron/oxygen) version: lighter, often more chemically tunable, and now explored for electronics as well as storage and gas separations. In October 2025, Google Scholar shows 1.810.000 results for MOF and 459.000 for COF.

But what makes these materials relevant outside a lab? Because a sugar-cube amount of some MOFs can have an internal surface area approaching a football field. That translates into practical superpowers: capturing CO2 from flue gas or air, storing hydrogen or methane more safely, trapping toxic industrial chemicals, accelerating reactions, and even harvesting water from desert air when paired with the right thermodynamics.

Crucially, this ecosystem of ideas is not confined to Berkeley or Kyoto. It actively includes Arab-world laboratories. At KAUST, Mohamed Eddaoudi leads one of the most prolific MOF programs, explicitly pursuing “made-to-order” MOFs for energy and environmental targets, down to angstrom-level pore tuning for trace CO2 removal. Eddaoudi co-authored the original MOF-5 breakthrough with Yaghi.

The Question of the Refugee: “Where do you come from?” and Scientific Horizons

Omar M. Yaghi is a Palestinian refugee born in Amman in 1965. His compelling background is rooted in displacement and poverty: the Palestinian refugee condition, now in its eighth decade, has routinely rendered uprooted communities invisible — their struggles and contributions discounted. His parents, who fled Gaza during the 1948 Nakba, faced many hardships in his childhood, including limited resources and overcrowded living conditions. His father raised cattle and owned a butcher shop in Amman. Despite his limited formal education, Yaghi’s father told him he needed to go to the U.S. He emigrated alone at the age of 15 and started his studies at Hudson Valley Community College. Later, he transferred to the University at Albany (SUNY) for his bachelor's degree and continued his education at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign for his Ph.D. An extraordinary educational journey for a stateless kid learning English on arrival.

Achievement never unfolds on level ground; privilege tilts the field, and inequality sets the course, long before talent is measured. That tilt is exactly what Michael Young warned about when he coined the term meritocracy in his 1958 satire “The Rise of the Meritocracy”, not as a celebration but as a warning: when merit is equated with testable intelligence plus effort, the winners naturalize their wins and the system forgets the starting line. In scientific careers, the starting line includes financial struggles, paperwork, visas, language, stable schooling, mentors, and safe labs; precisely the infrastructures that displacement puts at risk. Yaghi’s trajectory doesn’t vindicate meritocracy; it shows what becomes possible when unique circumstances and huge efforts occasionally counterbalance structural headwinds.

After pioneering reticular chemistry, Yaghi established the Berkeley Global Science Institute to promote research centers and opportunities for young scholars in under-resourced areas, including initiatives like The Olive Fellowship. Given his background, this gesture takes on even greater significance. Here, scientific excellence is not just about individual achievement but also about increasing access for those who start their journeys where he did.

The Nobel Prize: Prestige, Politics, and Swedish Gatekeeping

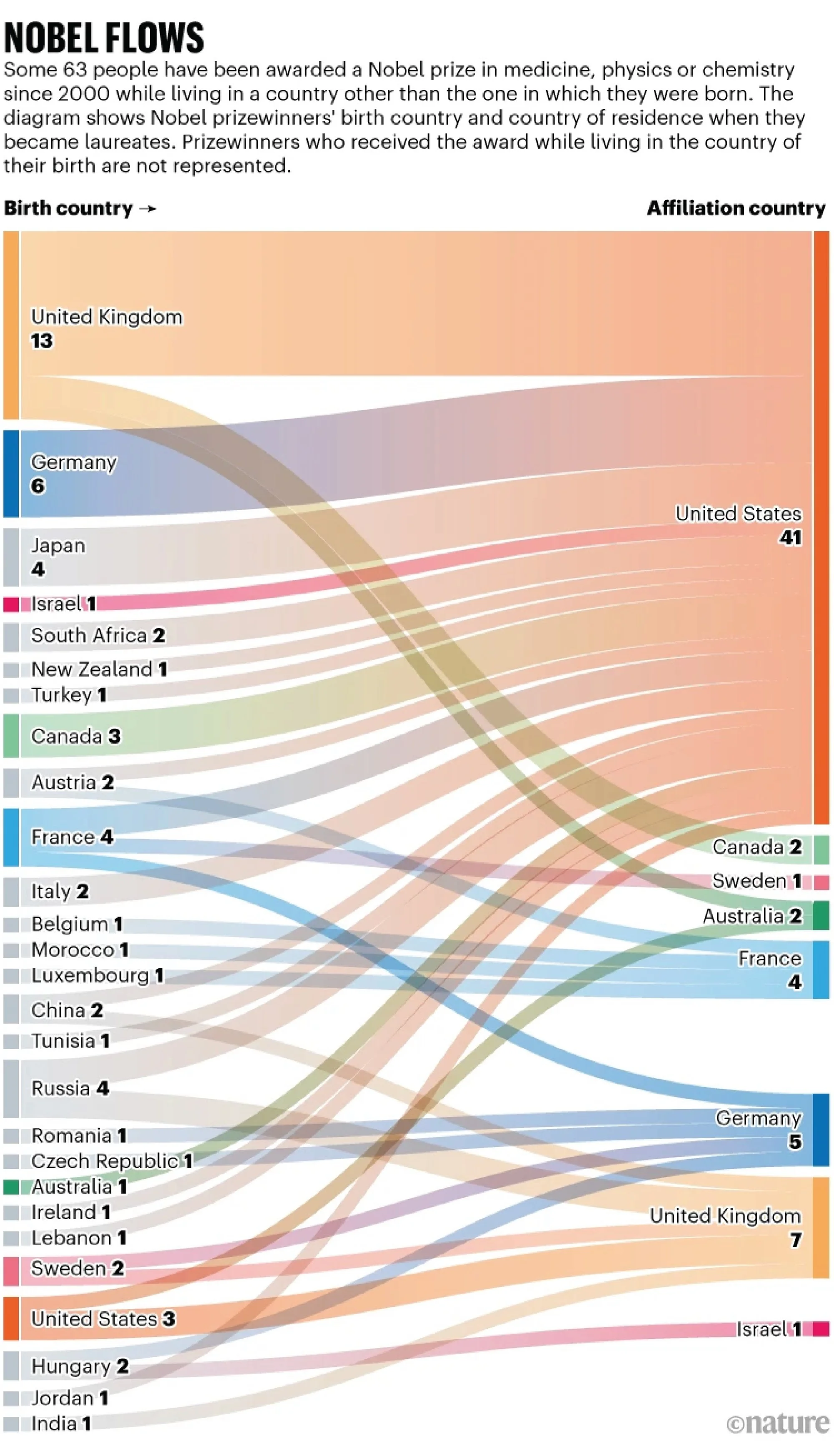

It is right to celebrate Yaghi’s win; it is wrong to forget who decides such wins. By Alfred Nobel’s will, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awards the Chemistry prize, acting on recommendations from a Nobel Committee for Chemistry elected by, and largely composed of Swedish professors. The committee screens nominations; the Academy votes. The structure centralizes agenda-setting influence within a small, culturally specific group, which explains the recurring critiques of Eurocentrism and limited epistemic authority, particularly concerning scientific awards.

Journalistic and scholarly analyses highlight several blind spots: geographic bias toward the North Atlantic, under-recognition of the Global South, and disparities by gender, race, and nationality among laureates. Christine Kerdellant and Daniel Temam, in “Prix Nobel, le prestige et l’imposture”, argue that the Nobel brand’s aura conceals these biases and controversies, transforming a human institution into an unquestioned arbiter of excellence. While significant, these issues do not diminish the prize’s importance; rather, they clarify its limitations.

It's fantastic that Omar Yaghi has received recognition, but let’s be clear: Arab scientists shouldn’t feel disheartened when the Nobel spotlight drifts elsewhere. These prizes are just spotlights, not definitive judgments. They often trail behind groundbreaking discoveries by years, yield to fleeting trends, and reflect the biases of those who hold the power to nominate and judge. When we focus on what truly matters (innovative ideas that cross borders, flourishing labs from Amman to Jeddah, and students who can envision themselves in this narrative), we see the impact is already real, Nobel or not. Our mission should be unwavering: to cultivate the conditions for excellence and recognition not only at home but throughout the region.

Worldwide Image and Representation: Why Yaghi’s Name Matters on the Podium

When Omar M. Yaghi steps onto the Nobel stage, several symbolic circuits close at once. First, his win punctures the deficit story about Arab science, linking contemporary laboratories in the region (think of the MOF powerhouse at KAUST) to the frontiers of global research. Second, it broadens who gets pictured when we say “scientist”, and the mental image of scientific authority becomes less monochrome — more familiar. It also reminds institutions that talent is unevenly funded, not unevenly distributed. Yaghi’s own route illustrates the civic payoff of accessible education that catches brilliance wherever it appears.

Awards don’t fix structures. But they do redirect attention. Yaghi’s Nobel points toward an idea (reticular chemistry, which gives us matter with otherwise impossible properties); toward labs (in Amman, Jeddah, Berkeley, and beyond that are part of the same conversation); and toward students (who can now see their own names as plausible on the world’s most famous shortlist).

About the Author

Safaa Elidrissi Moubtassim is a Moroccan researcher based in Spain. She holds a PhD in Nanoscience and Nanotechnology. She is currently the Afikra ambassador for the Marrakech chapter.