Between the Seen and the Felt: Nedim Kufi’s Visual Language

Words by Nour daher

Nedim was born in 1982 in Baghdad, a city that shaped his childhood—his first capital, not in the political sense, but in the emotional one. It is where his inner world began. When he speaks of his time there, his voice softens. “I wasn’t the kind of child who played,” he once told me. “I thought. I asked questions.” His father was his friend, treating him as an equal, letting him sit with adults and take part in their conversations. That early gesture of respect formed the seed of what would later become his artistic philosophy: an insistence on seeing, listening, and thinking for himself. In a world that demanded obedience, Nedim learned the quiet power of doubt and dared to question.

Absence, Meem Gallery Dubai 2010I have known Nedim for about five years now—long enough to recognize that his art is not something he makes, but one he lives through. To speak with him is to feel the same attentiveness that fills his work: words unfolding slowly, deliberately, like lines of graphite on paper, revealing meaning only after silence has done its part. There is a humility in his way of existing, a gentleness toward the act of making, and a restless curiosity that refuses easy answers.

The world around him was full of certainties he could not accept. He retreated inward, not out of despair, but out of inquiry. “I was always withdrawn,” he said. “Maybe it looked like isolation, but for me it was a way to think about life.” That solitude became his first studio—a place where the imagination could breathe before any material ever touched his hands. Studying fine arts was forbidden under the Ba’ath regime unless you were part of the Party — he was not. His father fought fiercely for him, proposing instead that he study music. Nedim refused. “My relationship with the world,” he said, “is through my eyes, through sight, and insight. البصر والبصيرة” The father listened. Respectfully, he took him to the Institute of Fine Arts in Baghdad, where Nedim saw for the first time that art could be taught, studied, and built like a structure.

Red Keyboard 2024 Doha Design

The discovery was both a shock and a liberation. But soon after came the Iran–Iraq War, and with it, the demand for military service. His classmates were sent to the front. Nedim, unwilling to be silenced by fate, wrote a letter to Saddam Hussein himself. In it, he argued that he could serve his country better as an artist than as a soldier. It was a dangerous act of defiance. “That letter changed my life,” he said. “It taught me how to speak to a dictator.” He used the language of diplomacy as a form of survival, crafting words like a poet, persuading through humility and precision. To his astonishment, the letter worked. A personal exemption arrived from the presidential office, allowing him to continue his studies while others went to war. It was his first lesson in the power of letters and words.

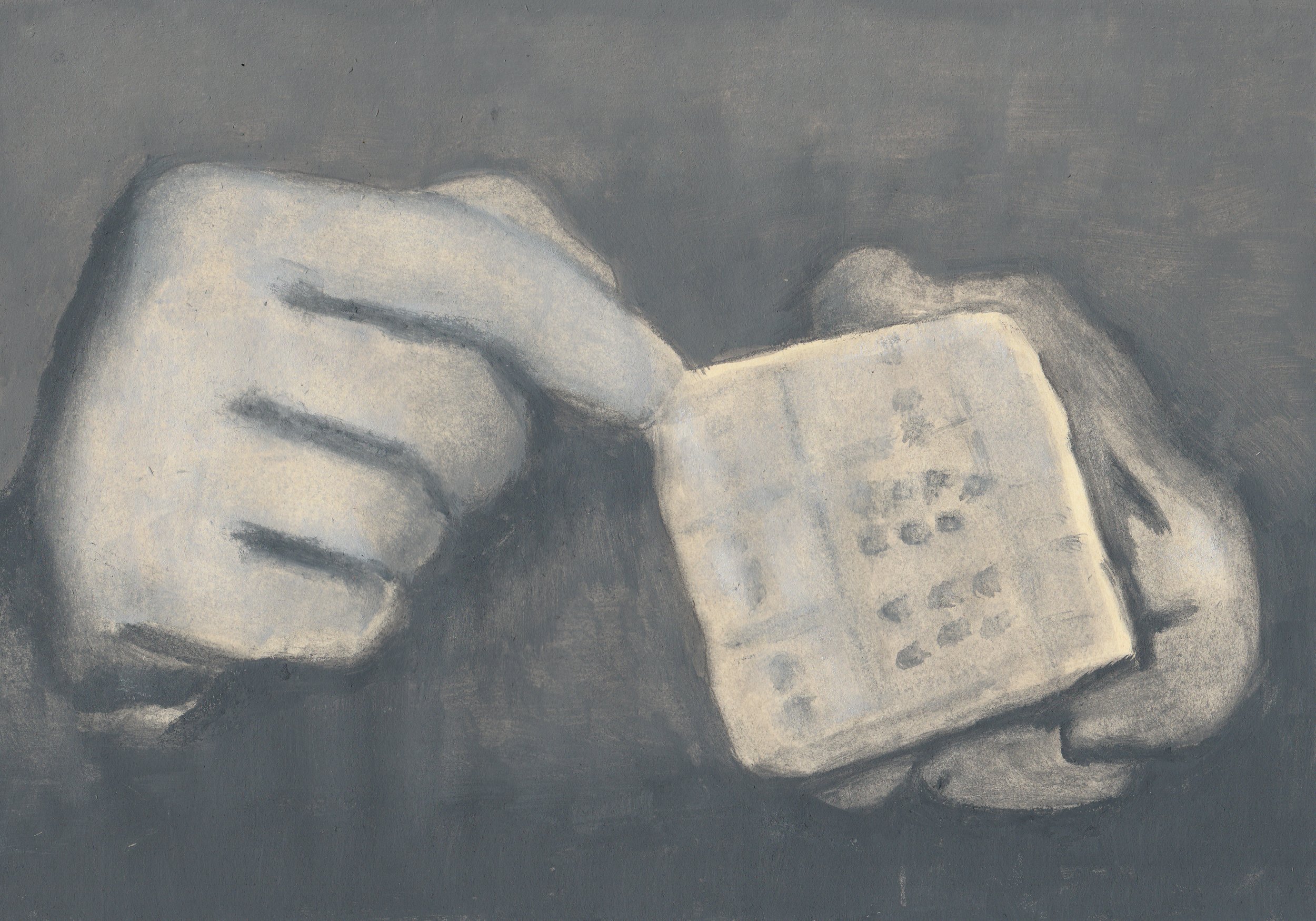

But the war still reached him. In 1985, after finishing the Institute, he was drafted for six months. During that time, he hid small sketches under his uniform. “Drawing for me was how I breathed in secret.” Years later, when he rediscovered those sketches, he felt as though he had found treasure. “They were like the alphabet of my existence,” he said. “Fire. A single fish. Simple words. The language of a child.” That purity—the refusal to become bitter or pitiful—became a lifelong stance. “I never accepted being seen as weak or humiliated,” he said. “Even under oppression, I felt full strength. I felt dignity.”

Those drawings, made in silence and danger, still feed him. They mark the beginning of his belief that to draw is to exist—that making art is not about beauty but about reclaiming freedom when the world denies it. In the years that followed, migration became both a reality and a philosophy. He left Iraq, crossing borders that seemed endless, moving through Tunisia and Morocco before eventually settling in the Netherlands. He often calls that time “the season of migration,” a phrase that holds both exhaustion and grace. “Migration gave me more than my homeland ever did,” he told me. “I threw myself into its arms, willingly.”

For many Iraqis, exile is a wound that never heals. But for Nedim, it was a rebirth. “Unlike the older generations who felt like fish pulled from water,” he said, “I came out of the river and lived again.” Migration taught him to see movement itself as a medium to understand that the act of leaving is also a form of creation, and the unknown is his subject.

"حذائي وطني أينما ارتحل”

His time in North Africa marked a turning point. In Tunisia and Morocco, he encountered a world “not taught in the academy,” one that challenged and expanded him. The music, the food, the rhythm of life in the Maghreb, all of it filtered into his work. He began keeping notebooks filled with sketches and writings, fragments of experience drawn in ink and memory. “Drawing was my way of traveling,” he said. “Even as a soldier, I would draw Azerbaijan, or Mexico. I didn’t know why I would only hear about them in the news or read about them in books. But when I draw, I move.” By the time he reached the Netherlands, his work had evolved into a language of its own. He no longer saw painting, design, or film as separate media — they were all different dialects of the same speech. His encounter with a French critic, who recognized in him a connection to Minimal Art, helped him name something he was already doing instinctively: reducing form to its essence, stripping away decoration to reach meaning.

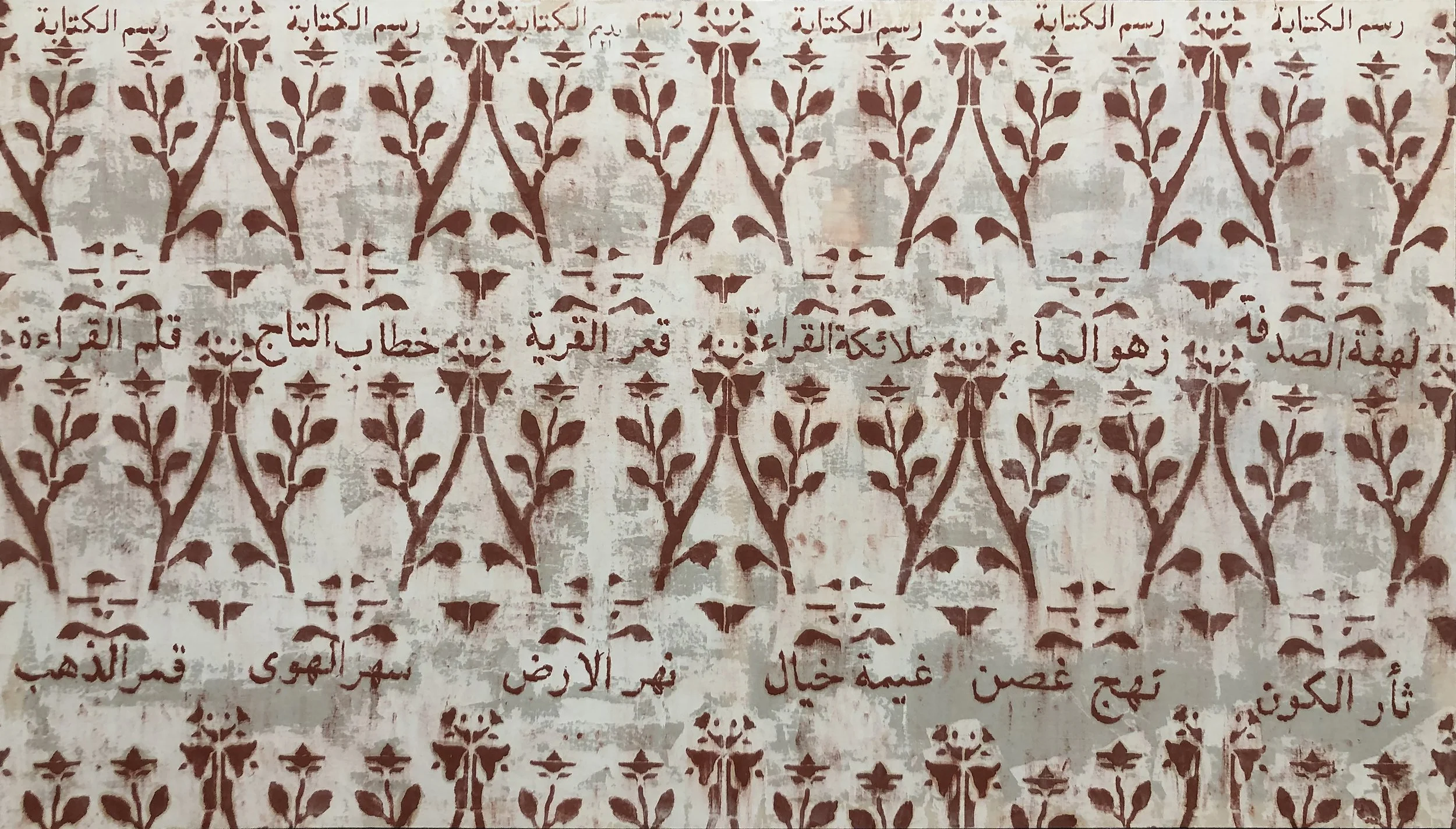

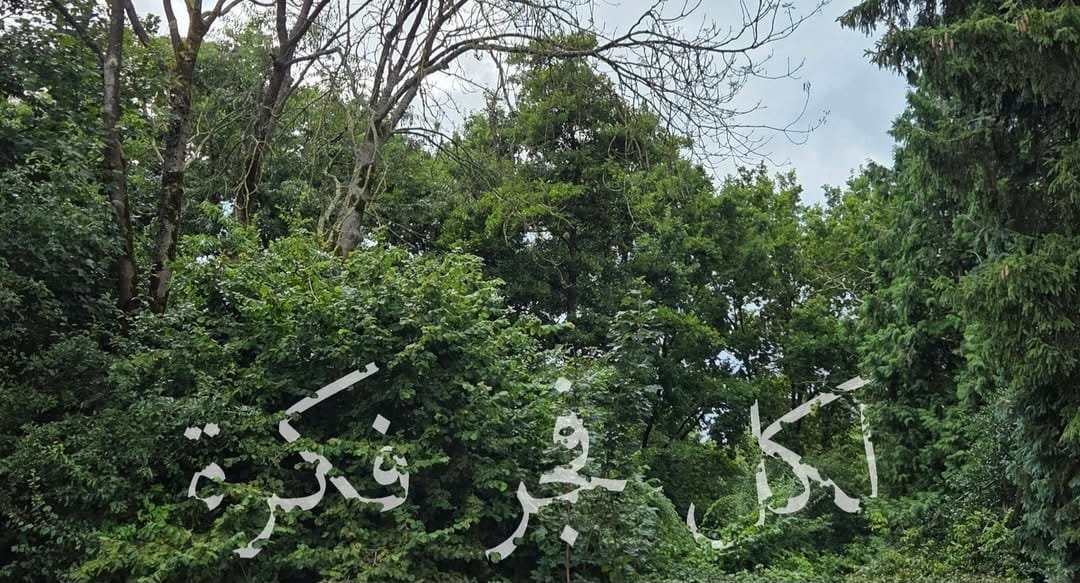

Nedim’s practice has since moved freely between media: painting, installation, video, and graphic design. He approaches each not as a field but as an opportunity to think differently. When he studied graphic design, he realized that art could serve communication. That it could open a dialogue rather than simply produce an object. “Design made me think with my head as well as my hands,” he said. “It connected me with people. It made me want to speak.” In his works, beauty is never the goal. He finds equal value in the awkward, the raw, the broken. “Sometimes ugliness expresses more than beauty, meaning always outweighs form, and wisdom matters more than admiration.” This philosophy runs through his work. To look at it is to sense that same blend of control and surrender. Whether through pigment, fiber, clay, or digital code, his works are acts of listening to materials, to memory, to the silence between ideas…In his hands, nature becomes language: leaves turn into letters, mud records memory, date pits become seeds of time. Nothing is inert: every element carries a story waiting to be revealed.

Underlying all of this is the experience of exile, not only geographic, but existential. To live between worlds is to inhabit absence, and Nedim has turned absence into a home. He no longer mourns what was lost — he studies it. Through collage, film, and editing, he turns memory into a space of transformation, where imagination replaces nostalgia. In this way, absence becomes not emptiness but potential, a place where belonging can be reimagined.

Perhaps what I admire most about Nedim is his resistance to vanity. “The ego can block your way without you noticing,” he once said. “You think you’re strong, but you’re just standing still.” His awareness of this trap keeps him grounded. Through that humility, he reaches universality. His abstraction is freedom rather than obscurity — a collaborative act of meaning-making shared between artist, audience, and universe. Over the years, I’ve come to see his art not as a collection of works but as a single, continuous act of becoming.