Resisting Erasure: Armenian Embroidery in the Diaspora

Words by Hrag avedanian

In a bazaar in the old town of Gaziantep—a South-central province of what is now Turkey—I came across embroidery that I would typically see in Armenian households in Lebanon, where I was born and raised. This shouldn’t have come as a surprise, as many Lebanese Armenians trace their roots to Gaziantep, or as the Armenians call it, Aintab. But it did. The vendors were also perplexed by this young male “tourist”’s fascination with the art form. At that moment, all I could think about was how the Armenian population, which was once an undeniable component of Aintab’s intricate and diverse social fabric, was no longer present in its old town. Yet, the embroidery stayed behind.

The northern districts of Aleppo in 1936. Refugees’ shacks appear in the foreground with newly built urban housing in the background, rferl.org

The embroidery of Aintab, or in Armenian Aintab-i kordz (literally “work of Aintab”), is one of several traditional forms of Armenian embroidery that we have inherited from our elders. Despite some having specific names, Armenians intentionally refer to traditional patterns or compositions by their place of origin—once Armenian settlements of the Ottoman Empire, all currently within the borders of modern-day Turkey. For example, Van-i kordz is the embroidery of the region of Van (or Vasbouragan), around Lake Van. Urfay-i kordz is the embroidery traditional to Şanlıurfa or Urfa. Svaz-i kordz comes from Sivaz or Sepasdia, and Marash-i kordz comes from Marash, or Kahramanmarash as it is known presently in Turkey. It is an unusually close interplay of textile art, geography, and nomenclature. For Armenians, as for Palestinians, embroidery is not just a form of applied arts, but rather a statement of belonging. It is a proud manifestation of a people’s identity and connection to their land: it is a material passport into what was once a homeland.

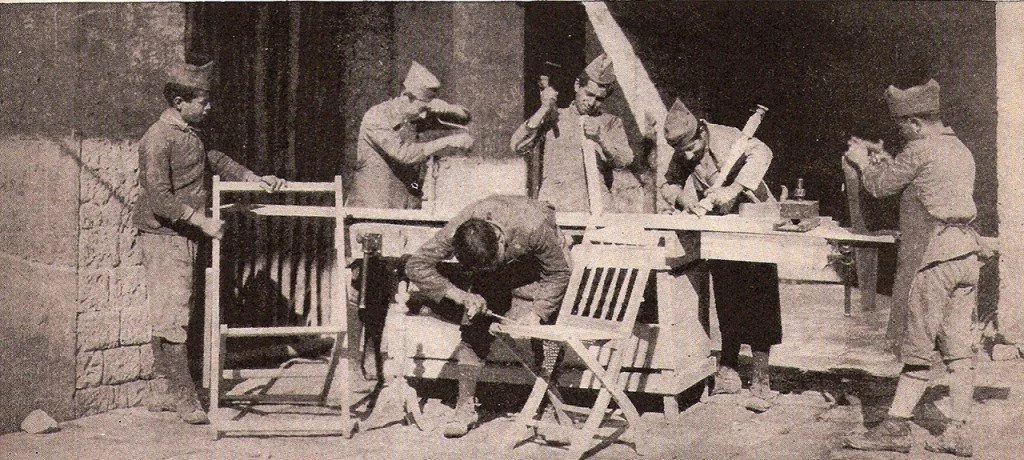

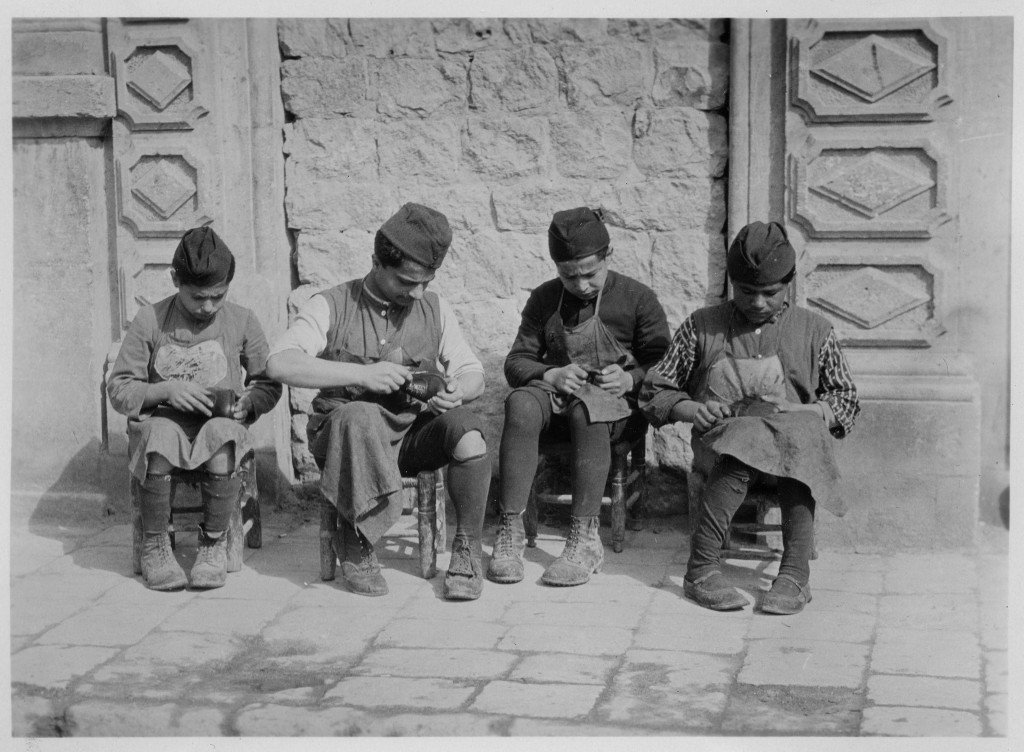

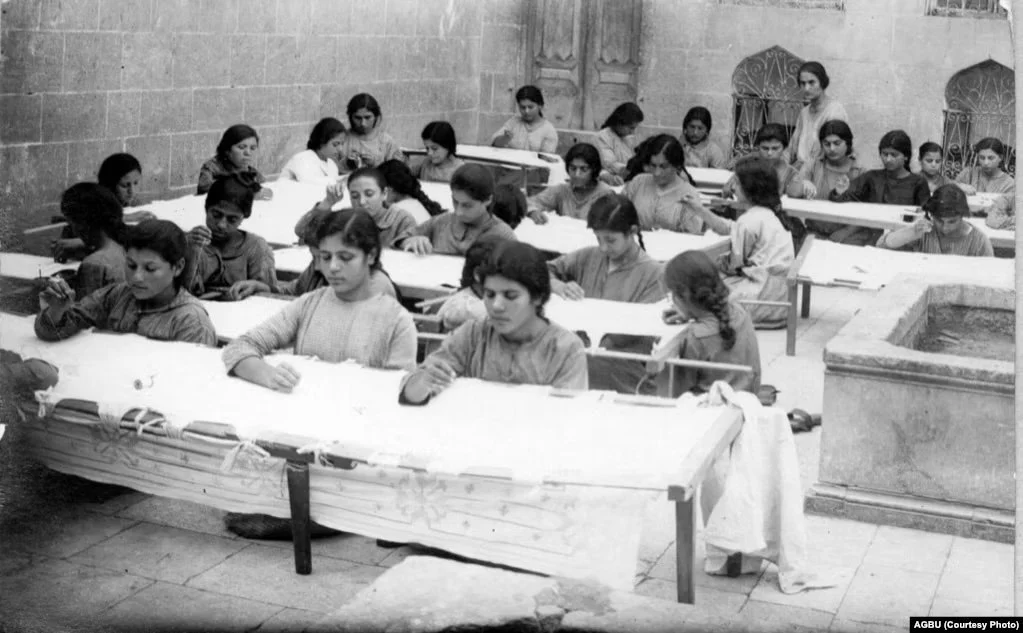

1- Young Near East Relief orphans training as cobblers in Aleppo, c. 1923. Photo from the Near East Relief Musuem -2- Apprentice Armenian shoemakers in Aleppo's Giligian orphanage and vocational school in 1923. Photo from the AGBU Collection -3- Apprentice embroiderers at Aleppo's Armenian orphanage in 1923. Photo from the AGBU Collection

A quick historical interlude might be helpful for context. In 1915, the Ottoman state ordered what they called the “safe relocation” of the Armenian population of Marash, Aintab, Van, Urfa, Svaz and other regions of the Ottoman Empire, which had a concentrated Armenian population. The destination was the deserts of Syria: Raqqa, Der-Ez-Zor, and Ras El Ain. Massacres and plundering of Armenian towns and villages followed. The Armenians of Cilicia, near the Mediterranean, sought refuge in northern Syria and Lebanon. They organized themselves in new Armenian settlements across the Arab world, such as Aleppo's Nor Kugh (meaning “new village” in Armenian) and Suleimaniyeh neighborhoods; Lebanon’s Nor Marash (meaning “new Marash”) or Nor Cilicia (meaning “new Cilicia”) neighborhoods in Bourj Hammoud; and in the Armenian Quarter of Jerusalem's Old City. With the forced displacement of Armenians, their crafts and traditions traveled with them.

Aleppo - a two-hour ride (97 km) south of Gaziantep - became the epicenter of traditional Armenian embroidery, where refugees from Aintab, Marash, Adana, and Hadjin were exposed to each other’s crafts and embroidery. Embroidery soon became a form of livelihood for women. Organized groups and workshops, such as the Elim House in Aleppo’s Seirafi neighborhood, emerged. Christian missionaries from Europe and the American Near East Relief arrived to help the displaced and orphaned Armenians. They established orphanages in Syria and Lebanon, which also served as ateliers to teach and produce traditional embroidery and carpets to Armenian girls and other forms of handicraft to the boys, such as carpentry or shoemaking. The products made by these orphans found a favorable market in Europe, with the French soldiers and officers who were stationed in Syria and Lebanon as part of the French mandate. Some of the proceeds were even used to buy land and to improve the living conditions for the refugees.

Embroidery by Vosgi Rapalian (née Mgrdichian) or Vosgi’s mother Yeghis Mgrdichian. houshamadyan

In December 2025, the Aintab stitch (Antep İşi in Turkish) was inscribed on UNESCO's Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity as a tradition of Gaziantep, Turkey. The listing bears no mention of Armenians, despite it being part and parcel of Armenian textile art. If one were to investigate, they would possibly find more varieties and heirlooms of Antep İşi outside of Gaziantep, particularly in the Armenian Diaspora around the world.

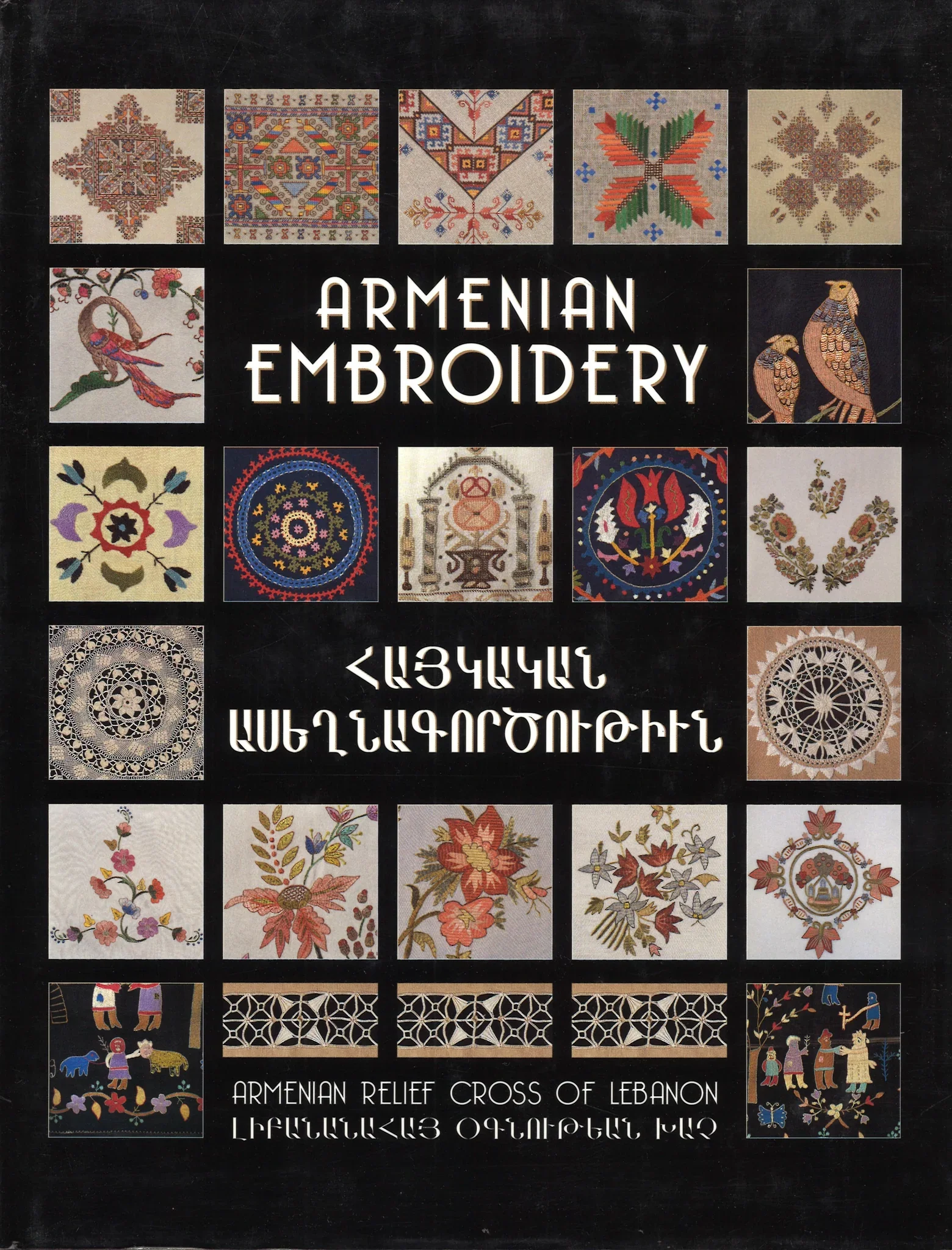

A quick look into Houshamadyan.org, an online platform that aims to reconstruct Ottoman Armenian life, will generate multiple examples of material culture, objects of memory, and heirlooms in the form of Ainteb embroidery in private collections in Armenian households. In 1999, the Armenian Relief Cross of Lebanon (ARCL), a women-led social organization, published a catalogue entitled “Armenian Embroidery,” which documents the different Armenian stitches, designs, and patterns with colored photographs of embroidery gathered from the elders of the community, many being from Ainteb. In Syria, impressive dedicated volumes to each of Marash, Urfa, and Aintab stitches were published, documenting the delicacies of the art form and presenting the cherished pieces of embroidery as inherited from mothers and grandmothers. The publication of these volumes is a testament to the rich Armenian contribution to traditional arts and crafts in the Middle East. The Armenian Museum of America and the History Museum of Armenia have their own impressive collections of embroidery.

Marash Embroidery in its two main types of stitches at the ARCL Artisanat Armenien in Bourj Hammoud. Photo by Jonathan Wuthrich

A century after the Armenian Genocide, the tradition of Armenian embroidery, including that of Aintab, lives on. Not just as a cultural art form, but also as an embodiment of collective memory—as an act of resistance to erasure. Every Armenian household in Lebanon, Syria, or Palestine would have an embroidered piece. It could be a tablecloth or a runner on the piano. It could be the alphabet, framed and hung on a wall. It could be in the form of a cross used as a decorative piece. Whatever form it takes, it remains a piece of the homeland in exile.

This essay is a brief visual and descriptive introduction to different types of Armenian traditional embroidery. An important disclaimer is that there is no one definitive source or naming of the different types of stitches, including some disagreements between Syrian-Armenian and Lebanese-Armenian communities, which is also a product of the genocide and the diffusion of folk knowledge. Moreover, borders were less rigid in the past. Many of these Ottoman Armenian regions were adjacent to each other, and there was constant friction, exchange, and cross-influence.

Aintab Embroidery with needlework lace (20th century). Property of Makroohi Chederjian who worked as a housekeeper at the Near East Relief Orphanage in Malatia, Turkey, where Armenian orphans were taught to embroider. Collection of the Armenian Museum of America

Aintab Stitch

The embroidery of Aintab is a special type of threading, drawn thread embroidery, which involves delicately pulling out threads or fibers from a plain cotton cloth, often white, off-white, or beige in color. It is counterintuitive in the sense that rather than adding stitches to the cloth, a pattern is made by first “carving out” desired geometric shapes of diamonds, squares, and triangles from the base piece of fabric. It is sophisticated, as was Aintab at the time, hosting the prestigious Central Turkey College, founded by American Missionaries, with a high Armenian enrollment in the student body. The stitch is laborious. The weaver will need to have a master plan in mind, resembling architectural grids. The removed spaces are then supplemented and enhanced by adding different types of stitches to the fabric, using neutral colored threads. It is delicate: if too many threads are removed from the fabric, one will have to restart the work from scratch. While not a colorful feast for the eyes, it is considered a masterpiece given the effort it takes to make it, and the market price reflects that.

Marash Stitch

Marash Embroidery (Irga) by Miriam Mukhitarian c. 1910. Collection of the Armenian Museum of America

Marash was known for cotton cultivation and processing. The school of Marash embroidery has two main types. The first is the common flat or level stitch—Hartagar in Armenian—found across different schools of embroidery, also referred to as Atlaslama in Syria. It allows the stitching of complex design compositions on the textile. This is why its patterns are not bound to fauna and flora only, but can also embroider human figures. In that regard, the “Wedding Scene” is a common composition. The second type of Marash stitch is the “secret” stitch (Kaghdnagar in Armenian), also known as woven stitch (Hyusvadz gar in Armenian)—peculiar only to Marash—known as Irga in Syria. In Lebanon, the term “Irga” is sometimes used to denote the first type. The second stitch can also be seen in Malta and parts of India.

Striking colors are often used in the Marash thread with black, dark blue, or brown backgrounds. Nowadays, velvet is the common choice of fabric. The design is first drawn or imprinted. The secret stitch starts with dots. Dots are then interlinked through woven threads to resemble small crosses. These crosses multiply to form geometric shapes of the desired design. The central motif of a Marash design was usually a circle known as “Sun” or “Rose”. The stylized Sun is a recurring motif in Armenian art, a remnant from its pagan past.

In the multi-ethnic setting of Marash with Armenian, Turkish, Greek, and Jewish inhabitants, the lingua franca (the common language adopted or spoken) was Turkish. As such, many of the motifs in the Marash stitch actually have Turkish names. For example, Bardakli (meaning teacup-like) or Saatli (meaning clock-like from the Arabic word ساعة). Other motifs have Armenian names like the MenMen, which resembles two juxtaposed italicized lowercase “m” letters of the Armenian Alphabet—pronounced “men” in Armenian. In today’s Marash (Kahramanmarash of Turkey), unlike in Gaziantep, the two traditional embroidery patterns do not exist. Some argue that it is due to the cross-like pattern that the Muslim communities did not adopt.

Ourfa Stitch

The embroidery of Ourfa has a majestic character. If made by a master embroiderer, it would be virtually impossible to tell which side is the back and which is the front. The type of stitch used is called Litsk (literally meaning “fillings”), used to fill the ornaments on the fabric. The needle moves in a manner to produce a row of machine-style stitches (thread-void-thread-void) and then returns to fill in the voids. This allows the full picture to be embroidered on both sides of the fabric.

The patterns seen on an Ourfa piece are often floral (flowers, leaves, branches). Birds are also omnipresent. Motifs are not bound to geometry and enjoy a free flow. Silk is often used both as a thread and a base fabric. Gold or the darker shade of a color—pink, green, blue—is used for the borders of a motif to make it pop out, giving it a somewhat 3D effect.

Ourfa Embroidery at the ARCL Artisanat Armenien

Svaz Stich

The type of stitch for a Svaz or Sepasdia work is called Tarsgar (literally “backward” or “reverse”). It is worked on the back to have a full picture on the front side. It is most often worked on canvas as it makes it easy to count each thread. Keeping count is important as symmetry is key. There are two schools on how to sequence it. Some embroiderers start with a motif’s border with dark brown threads and then fill it with colors using a cross-stitch, flat stitch, and fillings. Others start with the colorful motif first and then complete it with the dark brown border. Motifs are geometric in form. A recurring central motif is the eight-pointed, colorful cross, symbolizing the sun-god Arek. In Syria, they sometimes attribute this style to Van.

Svaz (Sepasdia) Embroidery at the ARCL Artisanat Armenien in Bourj Hammoud. Photo by Jonathan Wutrich

Van Embroidery in Lebanon (ARCL) Photo by Jonathan Wutrich

Needle Lace: Aseghnakordz

Mariam Eghigian Haroutounian’s lacework, Province of Sivas, Haratunian-collection, houshamadyan

This type is no short of magic. There is no canvas or any fabric for the embroidery to be composed upon. There is only a needle, a thread, and the imagination of the embroiderer. The needle weaves through the thread itself, in the air, to make a spiderweb-like knotted pattern, often in the form of circles. The woven threads are so flexible that any figure can be achieved by alternating the tension or the rhythm of knots and the loops. Embroiderers can weave complete sentences using this stitch. The possibilities of patterns are endless. Lacework was also prepared to supplement the borders of the other traditional works of Armenian embroidery. It can be seen on clothing (collars), bed sheets, handkerchiefs, and pillow cases.

In family settings, the primary purpose of embroidery was not livelihood, but rather dowry. Preparing the dowry of a girl was a family affair—a communal ritual. The collective work of the women—the mother, aunts, sisters, and cousins—sometimes started as early as when a girl was born. It was their way of promising a better life to the newborn child. It was the contribution of every female member to the other. Embroidery was a space for the women to gather, rant, gossip, sing, but most importantly, transfer knowledge—not just of the art form, but of the way of living, of expectations of society. It was a space created by women for women where they had the decision-making power in a patriarchal reality outside that circle. Embroidery was a form of storytelling—a story told by women. A form of cultural heritage developed by women, preserved by women, and transmitted to generation after generation through women.

Photo by Jonathan Wuthrich

My maternal grandmother, Anahid Babikian, daughter of Garabed of Sepasdia (Svaz), was not any different. She passed away in early 2025 at the age of 92. She left behind a wealth of love and memories. Among her material belongings is a large tablecloth that she embroidered herself as a teenage girl as part of her own dowry in Lebanon. I was only told the story of this piece after her passing. The son of her father’s employer, a local Arab, had made his interest in matrimony with her clear. She politely refused as she wanted to marry a fellow Armenian—a common practice of exiled communities and minorities. The rejected candidate, seeing her embroider this large piece of fabric, questions what use is there for it if her future husband could not afford a dining table that large, as he currently could. My grandmother answers with a smile, saying they would lay the fabric on the floor and sit on it. Years later, she married a fellow Armenian, my grandfather, Missag Kavlakian. They lived in Bourj Hammoud’s Camp Arakadz neighborhood. And even though they didn't own a large dining table initially, they indeed used the embroidered piece on special occasions, like the baptism of their children.

That embroidered piece is with me now. I’ve inherited not just a piece of worked fabric, but a story crafted with threads and a needle. It is a material exemplification of an uprooted people’s desire to resist erasure—to start life anew. It is one of many embroidered pieces made by many Armenian grandmothers, some even anonymous, that carry intergenerational stories, trauma, and resilience. Pieces of fabric that have accompanied them in their chapters of displacement. Beyond floral patterns, these women have stitched memory, both personal and collective. Through their meticulous work and away from any spotlight or international recognition, they have documented our people’s textile heritage. They are the unsung heroes of the tradition of Armenian embroidery, be it of Ainteb or any other corner of the Armenian world.

Armenian Embroidery published by the ARCL (1999)

Arpi Mangassarian of Badguer, explaining to her visitors the different types of Armenian Embroidery. Photo by Jonathan Wuthrich

For readers interested in learning more about Armenian embroidery, below is a link with a list of resources from Lizzy Vartanian’s platform that aims to promote and educate on the history of Armenian embroidery, while also bringing it into the future:

https://armenianembroidery.com/pages/resources

About the author:

Hrag Avedanian is a Lebanese-Armenian storyteller based in Beirut. With a background in political science, he explores the intersections of art, politics, and culture. In 2019, he established walking tours of Bourj Hammoud, highlighting the city’s Armenian historical, culinary, and cultural heritage.