Transnational Inspiration or Appropriation?: A Critical Examination of Arab Cultural Exchange & Extraction in Fashion

Words by Joelle Firzli

The history and culture of the Middle East and North Africa have long captivated Western explorers, artists, and writers, offering fashion designers a seemingly inexhaustible source of inspiration. From the ruins of Palmyra to the medinas of Casablanca, Western fashion has repeatedly returned to Arab visual culture in search of novelty, sensuality, and mystique. Yet beneath this enduring fascination lies a more important question: does Western engagement with Arab culture represent genuine cross-cultural dialogue, or does it amount to a systematic extraction of aesthetics divorced from their cultural, religious, and historical meanings? Debates around cultural appropriation suggest the relationship is far more complex than simple inspiration. This essay traces the evolution of this dynamic through key moments in fashion history, examining how Arab visual culture has been imagined, consumed, and frequently commodified by Western designers.

“One must go to the Orient, all great glories come from there,” Napoleon Bonaparte declared in 1798, a statement that would reverberate through Western culture for generations. Although his military campaign in Egypt and Syria ultimately failed, it succeeded in embedding the “Orient” within the European imagination. The expedition brought with it scientists, artists, and scholars tasked with documenting Egypt and producing an archive that blurred empirical study with fantasy.

By the early 19th century, Orientalism had crystallised into a distinctly Western construct. As later articulated by Edward Said in his book Orientalism (1978), it was less a reflection of lived realities than a projection of Western desire: a hybrid of fact and fiction shaped by power. Palaces in Damascus, imagined harems in Constantinople, deserts, Turkish baths, sensual women, Mediterranean light, and eternal sunsets populated a visual economy that defined the East as exotic, passive, and “other.” The Orient became a site of projection for Western artists, offering both escape and creative license.

In Arab and Middle Eastern societies, dress has never been merely decorative. Clothing historically encoded social status, religious values, climate, and customs, particularly modesty and humility. Garments were often loosely constructed, layered, and designed to obscure rather than emphasise the body. Tunics, long-sleeved robes, voluminous trousers, and wrapped silhouettes formed a shared sartorial language across regions and genders. Western fashion, however, engaged with these traditions without regard for their cultural logic, drawn instead to the visual exoticism of distant forms.

The early 20th century transformed the Orient into a laboratory for artistic experimentation. Between 1899 and 1904, Doctor Joseph-Charles Mardrus published a new French translation of The Arabian Nights, and in 1909, Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes arrived in Paris. Together, they offered audiences the illusion of travel without departure. Léon Bakst’s set and costume designs for Shéhérazade proved particularly influential. Drawing loosely from Persian miniatures while borrowing freely from Turkish, Chinese, and Indian ornament, Bakst produced a deliberately fantastical vision of the East. The stage overflowed with emerald and sapphire drapery, moucharabieh-inspired screens, hanging lamps, carpets, and cushions, an immersive spectacle of excess. Bakst’s costumes bore little resemblance to Arab or Ottoman dress. Instead, they were theatrical inventions designed to seduce Western audiences. Parisian women quickly embraced the look, and Bakst’s aesthetic became a blueprint for fashion.

Costume Design for a Eunuch in Scheherazade Léon Bakst Russian, born present day Belarus 1912. Metropolitan Museum of Art

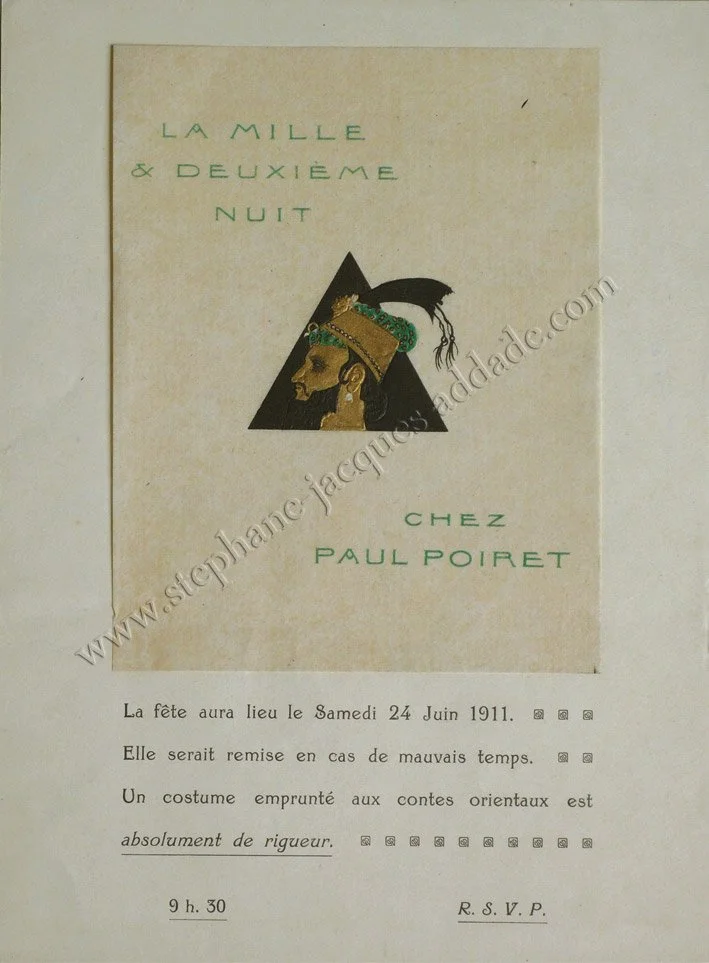

By 1911, French couturier Paul Poiret had positioned himself as the arbiter of Orientalist fashion in Paris. He popularised turbans adorned with aigrettes and reinterpreted the şalvar (sherwal), traditional Ottoman trousers originally designed for modesty and mobility. Beginning in the 1910s and early 1920s, Poiret transformed the şalvar into a luxury garment for Western women, severing it from its functional and cultural origins. At his hôtel particulier on rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré in Paris, Poiret staged lavish masquerade balls, including the infamous Bal de la Mille et Deuxième Nuit, that transformed his home into a theatrical Orientalist set. Guests arrived in Bakst-inspired costumes, consuming Arab aesthetics as spectacle. These salons crystallised enduring stereotypes: sexual excess, submissive women, idleness, and mysticism, rendered fashionable through couture.

Invitation 1002 nuits Poiret

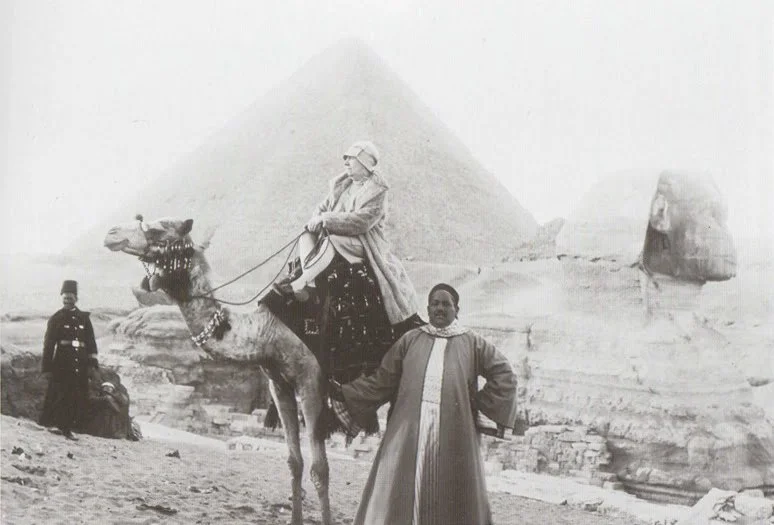

Jeanne Lanvin in Egypt, 1920s

Christian Dior spring 2004, couture 00010h, Erin-Oconnor

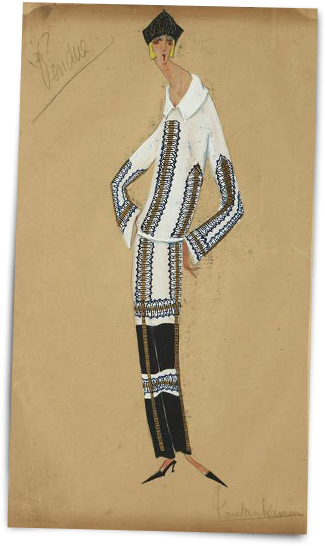

© Patrimoine Lanvin. Lanvin, Collection Toutankamon 1923

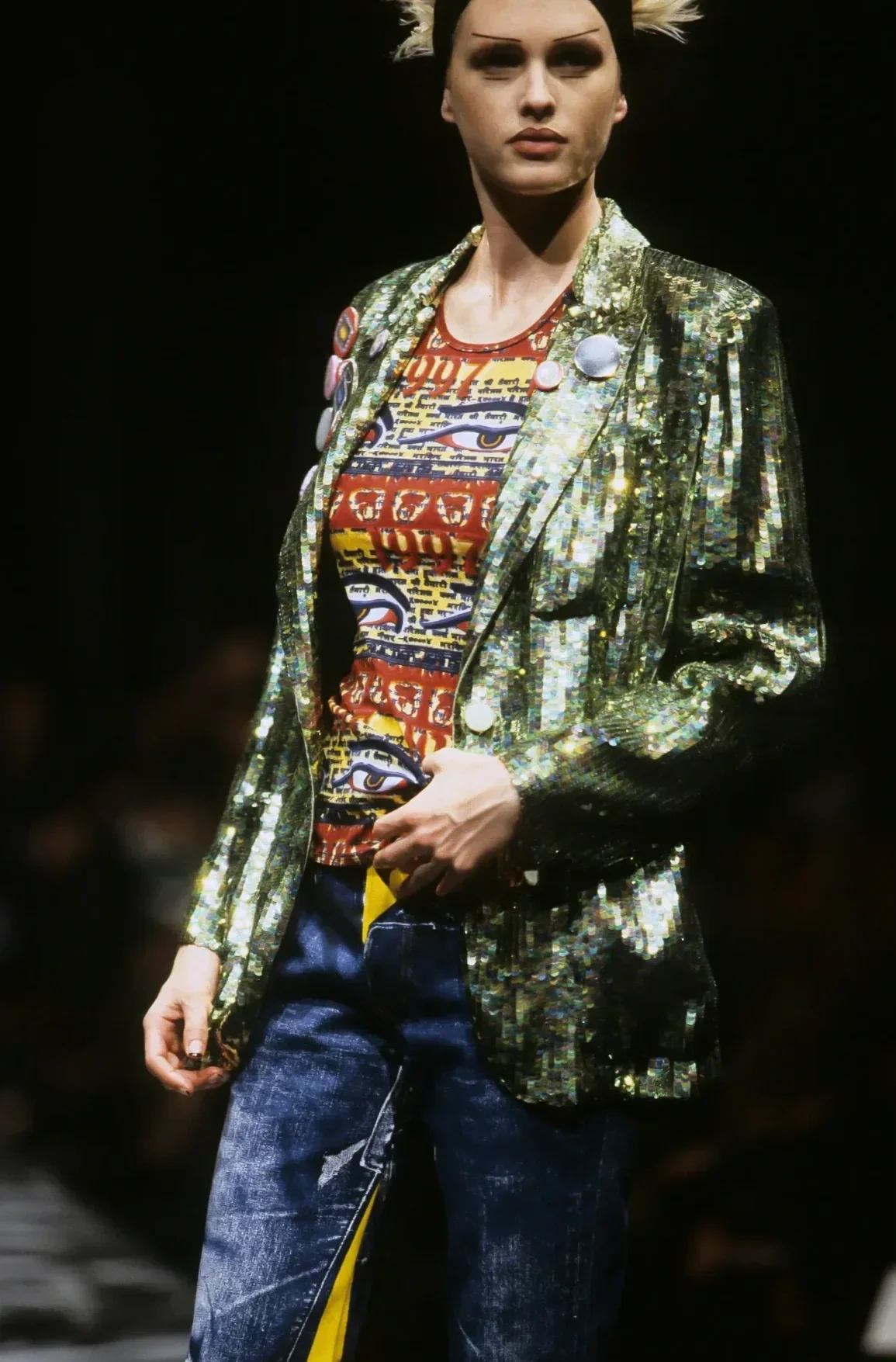

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, European archaeological expeditions systematically removed Egyptian antiquities to Western museums. The 1922 discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb intensified this extraction and sparked Egyptomania across Europe, a craze that quickly reached fashion. Parisian jewellery houses, including Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels, produced collections inspired by scarabs, hieroglyphs, and deities, translating sacred symbols into luxury objects for Western elites. French designer Jeanne Lanvin—after visiting Egyptian ruins—presented her Tutankhamun collection in 1923, incorporating archaeological motifs into couture. These gestures functioned less as homage than as acts of cultural authority, reframing Egyptian heritage through Western luxury systems. This obsession with Egypt persisted into the late 20th century. Jean Paul Gaultier’s Spring/Summer 1997 collection featured a distinct Egyptian theme, heavily incorporating iconic imagery like the Eye of Horus, scarabs, and hieroglyphs into bold prints on dresses, tops, and trousers, often in rich browns, blues, and golds. In 2004, Christian Dior’s Egyptologie couture collection explicitly revived colonial fantasy, positioning Egyptian heritage as raw material for Western luxury production.

Elsa Schiaparelli robes Hammamet

In the 1930s, Italian fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli developed a more sustained relationship with North Africa, spending extended periods in Tunisia. She drew inspiration from local dress, including sheer robes worn in the Hammamet region. While her engagement was deeper than that of many contemporaries, it nonetheless reduced complex garments to aesthetic motifs detached from social meaning.

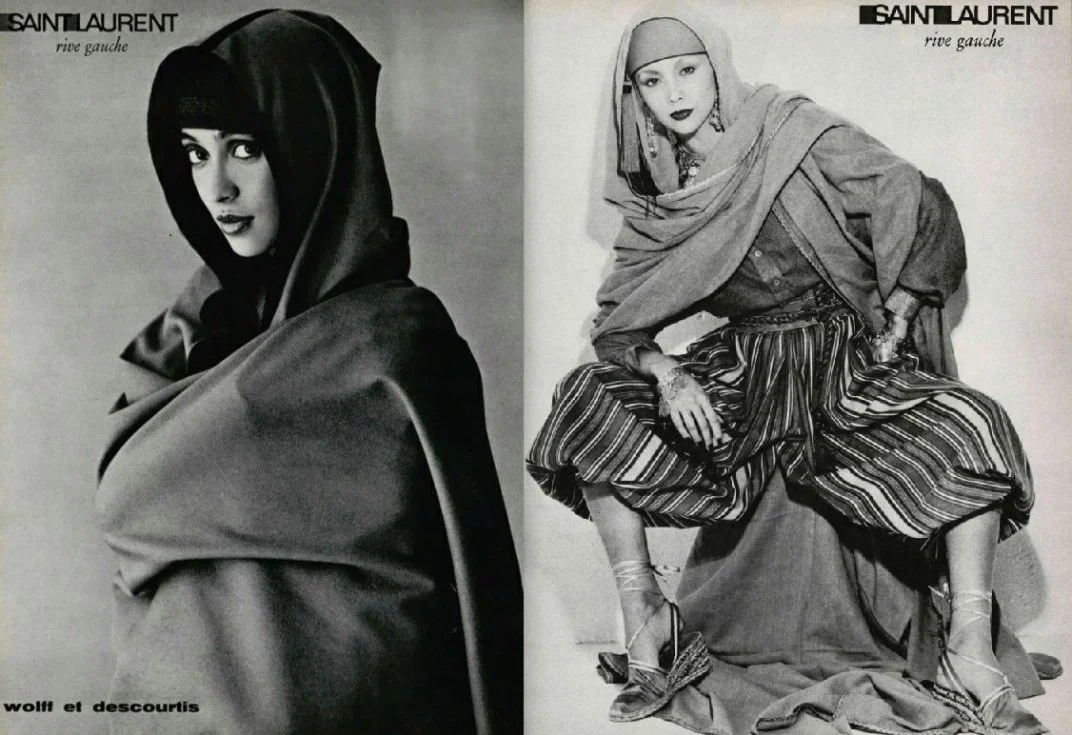

Yves Saint Laurent marked a turning point. Born in Oran, Algeria, and identified as a pied-noir, his relationship to North Africa was shaped by colonial proximity. After his first trip to Morocco in 1966, the country became central to his creative life. Saint Laurent reinterpreted the djellaba, introduced scarf-like head coverings referencing the hijab, and revisited the tarbush (fez), softening its form into a Europeanized accessory. Though more informed than many designers, his work still imposed Western fashion logic on garments rooted in different cultural systems. The House of Dior, under Marc Bohan in the 1970s, followed with Europeanized caftans, further normalising this authority.

YSL Red raffia and tassel hat 1976 from resurrection vintage-950

YSL 1960s

In the early 1980s, Jean Paul Gaultier collaborated with British milliner Stephen Jones. Their Spring-Summer 1984 collections featured a black felt masked hat directly inspired by the Moroccan fez. Transformed into a theatrical object with eye cutouts and cascading silk fringe, the fez’s cultural specificity was preserved visually but reassigned symbolically within avant-garde fashion.

Jean Paul Gaultier, Spring-Summer 1997, Runway

A Stephen Jones for Jean Paul Gaultier black felt masked-hat, Spring-Summer 1984 collections

Jean Paul Gaultier, Spring-Summer 1997, Runway

Karl Lagerfeld’s Chanel Spring-Summer 1994

Script-based inspiration surfaced prominently in Azzedine Alaïa’s Fall/Winter 1990-91 collection and Karl Lagerfeld’s Chanel Spring/Summer 1994 show. In both cases, Arabic and Kufic script, or pseudo-Kufic abstraction, appeared as ornamental elements on garments (in fact, European Renaissance artists lacking Arabic literacy adopted pseudo-Kufic lettering as decorative abstraction, a practice that obscured the meaningful cultural origins of these visual forms). The designers’ positioning differs significantly. Alaïa, Tunisian-born, engaged with script as a designer working from within North African visual culture. German-French designer Karl Lagerfeld’s Chanel collection, conversely, drew on Arabic letterforms as external reference points. This distinction raises important questions about authorship and cultural positioning in fashion design: how does a designer’s cultural proximity to a visual tradition shape the way that tradition functions in their work? When a script appears as an ornament in haute couture, what interpretive frameworks govern how it is read, as meaningful language or as abstract decoration? These questions suggest that the same formal element can operate differently depending on the designer’s relationship to its cultural origins.

Azzedine Alaïa’s Fall-Winter 1990-91, Costume Institute, Metropolitan Museum of Art

From the 1990s onward, luxury designers including Valentino, Donna Karan, and Givenchy incorporated Arab-inspired silhouettes and accessories into their collections. In 2009, Riccardo Tisci presented a revisited version of the battoulah (a distinctive face mask traditionally worn by women in the Gulf and Persian Gulf regions, that’s deeply connected to identity and heritage: wearing it is a marker of cultural belonging and respectability) on the Givenchy Couture runway, a decision that sparked immediate controversy. Vogue framed the collection as drawing inspiration from Morocco, “Berber” aesthetics, and equestrianism, noting that “the collection read in [a] conceptual and visual rather than literal ethnographic way.” In other words, the inspiration was conceptual and visual rather than documentary or anthropological. This parenthetical caveat (“not that the collection read in any literal ethnographic way”) seems designed to defend against accusations of cultural appropriation by suggesting the designer was not trying to authentically represent Amazigh culture, just draw aesthetic inspiration from it. It is a common disclaimer in fashion writing. The question still remains: is this distinction meaningful?

Givenchy Fall-Winter 2009 Couture

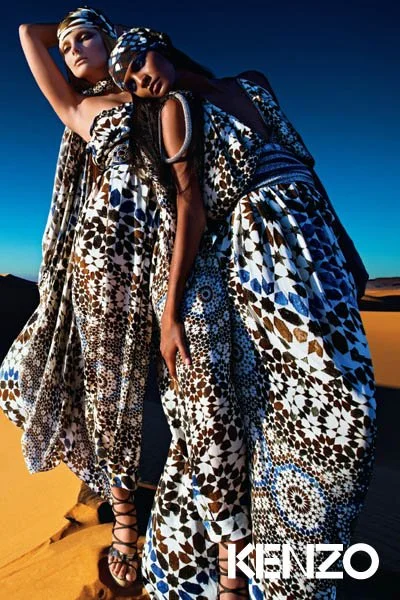

This pattern extended to Islamic architectural systems. Kenzo’s Spring 2010 collection appropriated zellige—the intricate geometric tilework fundamental to Islamic and North African design—translating centuries of mathematical, spiritual, and cultural significance into surface textile decoration. Both cases illustrate the same dynamic: traditional forms are borrowed, their meanings stripped away and repackaged as aesthetic ornament for Western consumption.

In 2016, Dolce & Gabbana entered the modest fashion market with its first collection of hijabs and abayas, silk-lined pieces adorned with the house’s signature prints of lemons, roses, and daisies, priced for luxury consumers. The collection was widely framed as a watershed moment: a major European fashion house finally acknowledging Muslim women as consumers. But critics questioned whether the collection represented genuine inclusion or merely another appropriation for financial gain. By stripping the abaya of its religious and social meaning, transforming it into decorative luxury wear.

Kenzo Spring-Summer 2010, Eniko Mihalik Liya-Kebede by Mario Sorrenti

Halima for Max Mara

That same year, Somali-American model Halima Aden walked the Milan Fashion Week runway in hijab for Max Mara and Alberta Ferretti, a moment fashion media hailed as groundbreaking. Her visibility suggested a real institutional shift. Yet the celebration obscured a structural reality: Western fashion houses determined the terms of that visibility. They decided when hijab registered as fashionable, which bodies could authentically present it, and what cultural narrative it would carry. By positioning themselves as interpreters of Islamic modesty, these Western luxury brands reinforced their gatekeeping role over representation.

Together, these moments reveal a consistent pattern: interpretive authority remains concentrated in Western institutions. Across two centuries, Western fashion’s engagement with Arab culture has followed a remarkably consistent pattern: admiration that reproduces asymmetrical power. Living cultural systems are reduced to aesthetic resources, borrowed and eroticized while authority over interpretation remains Western. The challenge is not whether designers may draw inspiration from Arab traditions, but whether they can recognise these as equal creative agents rather than aesthetic colonies to be mined. This requires not merely visibility but accountability, crediting sources, sharing authorship, and sometimes accepting that certain forms should not be borrowed at all. Until then, fashion’s Orientalism persists, renamed as appreciation.

About the author:

Joelle Firzli is a fashion scholar and part-time lecturer at Parsons School of Design. Her scholarship examines global fashion histories with particular attention to West African and MENA fashion practices, exploring the intersection between dress, identity, and power. She conceives fashion as a transnational form of cultural expression that centers untold narratives of non-Western fashion systems. Her work has been published in the Fashion Studies Journal, Studies in Costume & Performance, Vogue Arabia, and Business of Fashion. She holds a BA in Political Science from Lebanese American University and an MA in Fashion Studies from Parsons School of Design.