On Identity, Process, and Shifting Mediums: Q&A with Artist and Former Journalist Massoud Hayoun

Nour Daher: To begin, can you tell us a bit about your upbringing and how it shaped the way you see the world?

Massoud Hayoun: I was raised by my Moroccan-Egyptian and Tunisian grandparents in Los Angeles. They were of Jewish faith. My mother worked – frequently more than one job – to support us, so she wasn’t there for the parts of my childhood that were enjoyable. She just continually sacrificed her time and energy to feed my face and the capitalist machinery of this country at thankless, hourly wage jobs, lining the pockets of Republican bosses.

My grandparents were more or less socialist and compassionate. In their generation, people in the francophone world without much knowledge of China really admired Mao Zedong, largely on anti-colonial principle, especially at the time of the Algerian War for Independence. For that and other reasons, I learned Chinese from very young and eventually became a journalist in China. I didn’t have the right visa to practice journalism there, so I eventually had to come back to the U.S., and encountered a lot of people in my reporting across the country and in other countries I visited for several media outlets. These people, my grandparents, the news and a general simultaneous love and resentment of humanity are what guide my art practice. All of the above frequently feature in the paintings – sometimes all at once. And sometimes, I go off the rails and paint something that makes me laugh. I just painted a piece (“The Master’s Tools” – the title alludes to the Audre Lorde book) that expresses my frustration for having done nothing meaningful at all to help against the genocide of the Palestinian people. There are four iterations of my grandmother in this painting, one Argentine Mother of the Plaza de Mayo, women who have long inspired me, and incarnations of American consumerism.

ND: Your heritage spans multiple cultures: North African, Arab, Jewish, and American. How do these layered identities inform your work?

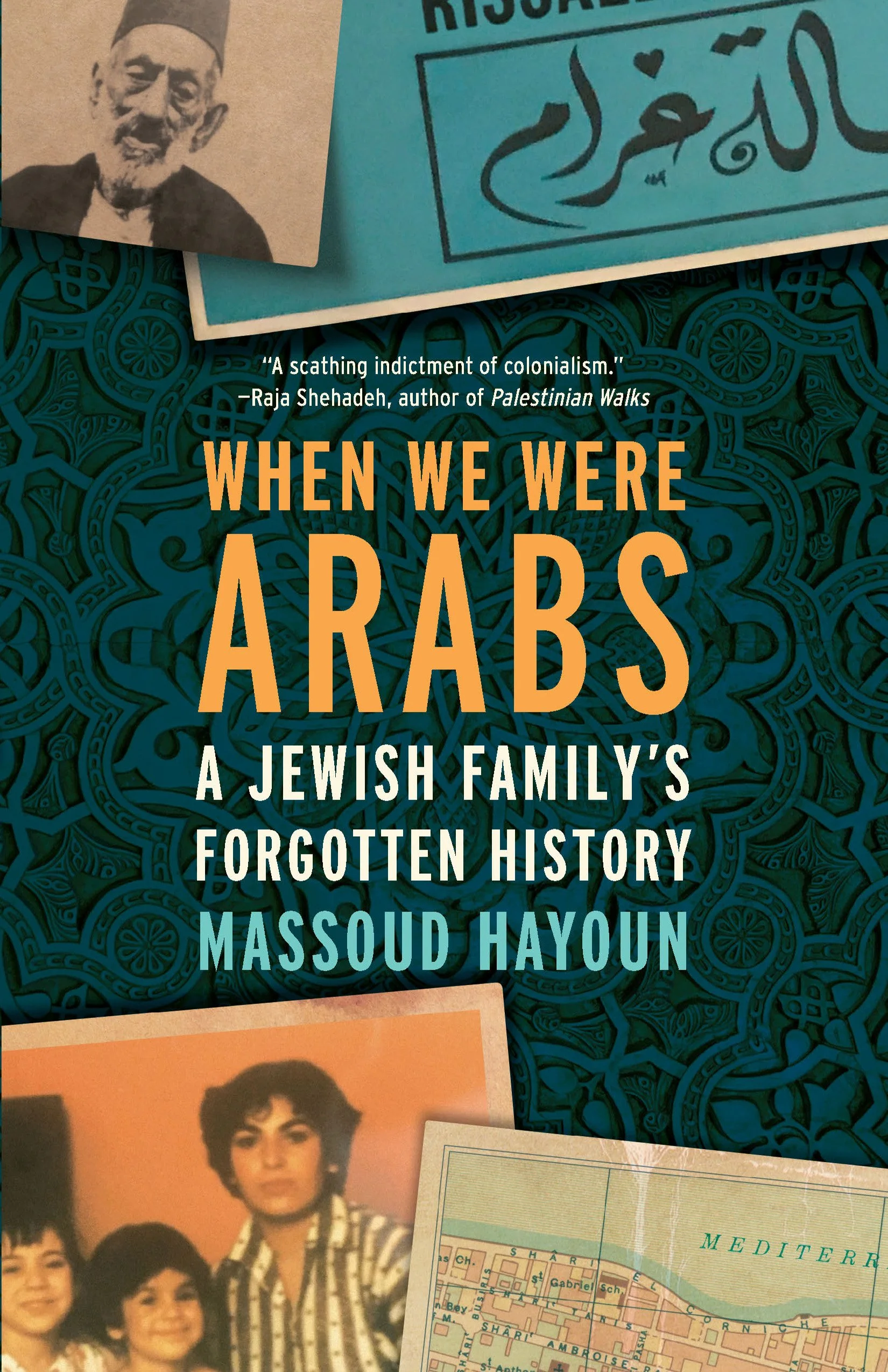

MH: In 2019, I published a book about Arabness from the vantage point of my place in this rare corner of the vast, diverse Arab peoples. It’s called When We Were Arabs. It won an Arab American Book Award for breaking new ground in Arab and Arab American Studies, was re-released in paperback this year, and will soon go into second printing. In that book, I explain why above any identity, I identify with Arabness as defined through conversations with people thinking critically about what this identity comprises, analysis of colonial policy documents, and revisiting my family history since time immemorial. The painting is in some senses a continuation of some of those ideas. But I’m done explaining myself to people. I did that in the book; if people care to read all about it, they can. Now I’m forging ahead, living my life.

ND: You began your career as a journalist and writer, and later moved into visual art. What sparked that shift in medium?

MH: A few things. First, around the time Al Jazeera America – where I was a Web reporter – ended. I moved back from New York to Los Angeles, where I helped to take care of my grandmother in her last years. I was still freelancing for Al Jazeera English from southern California/northern Mexico at the time. Then I focused on writing When We Were Arabs, which at first was meant to have been sort of co-authored with my grandmother. Two months after we got a book deal, she died, and my world became infinitely darker. I forged ahead and finished it, though.

In the 11th hour of her life, my grandmother started drawing for the first time: wild drawings – animals and flowers with wild, often hilarious back stories. She was very clear-eyed, very wry, until her dying day. I was inspired by her to take my artwork more seriously. I was emboldened by the idea that we can very drastically reinvent ourselves in the pursuit of expression, even very late in the game. I also wrote a pair of novels that came out with an Arab-British publisher. That was my pandemic passion project. Virtually no one read them, but Ai Weiwei endorsed one I wrote about Beijing, where we both lived at the same time. The force of speaking to him over FaceTime while he ate a peanut butter sandwich and discussed a bit of what role art should play in society pushed me to think more about pursuing art professionally. Then, like a journalist, I started going around LA, asking gallerists if it’s ridiculous for me to start trying to show professionally at my age and with a whole other career and educational background. Some responses were encouraging, some were disheartening. But I brushed off the latter pretty quickly. I felt the need to do this thing welling up within me. I enjoy that painting is an accessible medium. You don’t need the time, literacy or education necessary to enjoy a book and much of the news to enjoy a painting. You just need eyes, lived experiences, and maybe a sense of humor.

ND: How do you see the relationship between your writing and your visual work? Are they separate practices for you, or do they speak to each other?

MH: They definitely speak to each other. Without the experiences I’ve had on the road, reporting for different outlets, I wouldn’t have the thoughts that generate these paintings or know the people who populate them. And yet, none of these paintings would work in writing. It’s not like I’m doing my written work in a different medium. My brain works differently for both. I will say, with respect for my past, I was so terribly alone when I was writing. The reporting was a social practice, but the writing was a solitary thing. The painting – likely because it’s figurative – is much more invigorating. I feel myself to be more a part of the world and of humankind.

ND: Your visual pieces are often deeply personal but also political. How do you navigate that line between the intimate and the collective?

MH: Thank you so much for these intelligent questions – I don’t mean that to sound condescending. But it’s just a pleasure to respond to such considered and evocative questions. This is probably one of the ways in which journalism affects my art practice. When you write foreign affairs stories for a U.S. publication, there always needs to be a U.S. angle. If not, your editor will ask you: Why should Americans care? Something horrible happening in some far-flung place isn’t enough; basic decency, empathy or human solidarity is never enough for U.S. news editors. Maybe that’s one of the reasons why the U.S. is as it is today; we need to see every problem as personal for it to matter. For my paintings, I and my gallerist are my editor, but I’m still asking myself “Why do we care?” I am trying to move beyond my feelings and recognize that art doesn’t exist in a vacuum. I’m trying to make these paintings newsworthy, in that sense.

ND: Are there particular visual or literary traditions you feel you're in conversation with, or pushing back against?

MH: I am self-taught. So I try to hide myself away from any sort of education that might make my work less than a totally earnest expression of what’s happening inside. I am, as with When We Were Arabs, endeavoring to join myself to the voices of many other young, international Arabs envisioning what the future will look like after this moment of unthinkable carnage and destruction passes.

ND: Can you walk us through the beginning of a painting: what usually sets it in motion?

MH: The beginning of my paintings really resembles working on a news desk. At the start of every day on a news desk, you “read in” (read the news wires and what people are reporting on other sites), put different threads together, see what you can add to the conversation, think of your angle and pitch your editors a story. I still read the news, I wander LA witnessing people as people are, and I form a pitch to myself for a painting.

ND: What's next for you? Any projects you're currently working on or thinking through?

MH: I’m having a bit of a personal and political drama lately, further to your earlier question. Some of your readers may have heard that Los Angeles has been facing widespread deportation raids and that we are currently under military occupation from the federal government. I went to a protest against the attacks on immigrants like my parents in June. My mother was born undocumented, and my grandfather struggled to get papers for many years. The police said they issued a warning for the protestors at the rally I attended to disperse. I and my fellow protestors never heard it. We got arrested. I go to court next month, around the time of my 38th birthday. I’ve painted a three-panel painting about the arrest called 409pc, Failure to Disperse (the charge against me). We all thought the judge wouldn’t make us go to court for something so clearly designed to discourage would-be protestors from expressing support for our communities. But it looks like we will in fact go to court, so what will happen is anyone’s guess. This whole ordeal is generating a lot of artwork, so if they want to put me in prison for doing nothing illegal, I hope they’ve got art supplies, because I’ve got a lot to say.

ND: Who are the voices you feel in conversation with? What/who would you name as key influences on your practice?

MH: Ai Weiwei and my grandmother. Ai Weiwei is the king of art as a subversion of the status quo and the halls of power. I am working in his tradition, addressing different issues but the same machinery of injustice. And then my grandmother, because she was tough and brilliant like many Tunisian women I’ve met. And insofar as her life was a series of people trying to beat down that aspect of her, her life was a grand work of subversion.