The Casablanca Art School

The School of Fine Arts of Casablanca emerged in an exciting moment for Morocco, when the country was grappling with the possibilities and realities of its postcolonial identity. Out of this came an “urgency to reform national culture and its lingering colonial complexes” that filtered down into cultural production. Artists at this time were literally shaping what modern art could be, decolonizing and democratizing art, incorporating local heritage and tradition, and radically re-imagining how it could fit into society.

Exhibition view: Student Annual Exhibition of The Casablanca Art School, Fine Arts Gallery of the Arab League Park, Casablanca (June 1968). © M. Melehi archives/estate. Photo: M. Melehi.

History of the School

The School of Fine Arts of Casablanca (المدرسة العليا للفنون الجميلة بالدار البيضاء) was founded in 1919 by Edouard Brindeau de Jarny, a French Orientalist painter who had been commissioned by the French Resident General to catalog Moroccan visual culture. Under colonial governance, the school operated on a segregational basis that gave preferential treatment to the French. The school differentiated between students by ethnicity, gender and social status, meaning that Moroccan students were not allowed to exhibit their works and were pushed towards "useful" or practical artistic practices such as craftsmanship or design. Meanwhile, French students were encouraged to pursue fine art studies. At this time, all teaching staff were also required to hold French nationality.

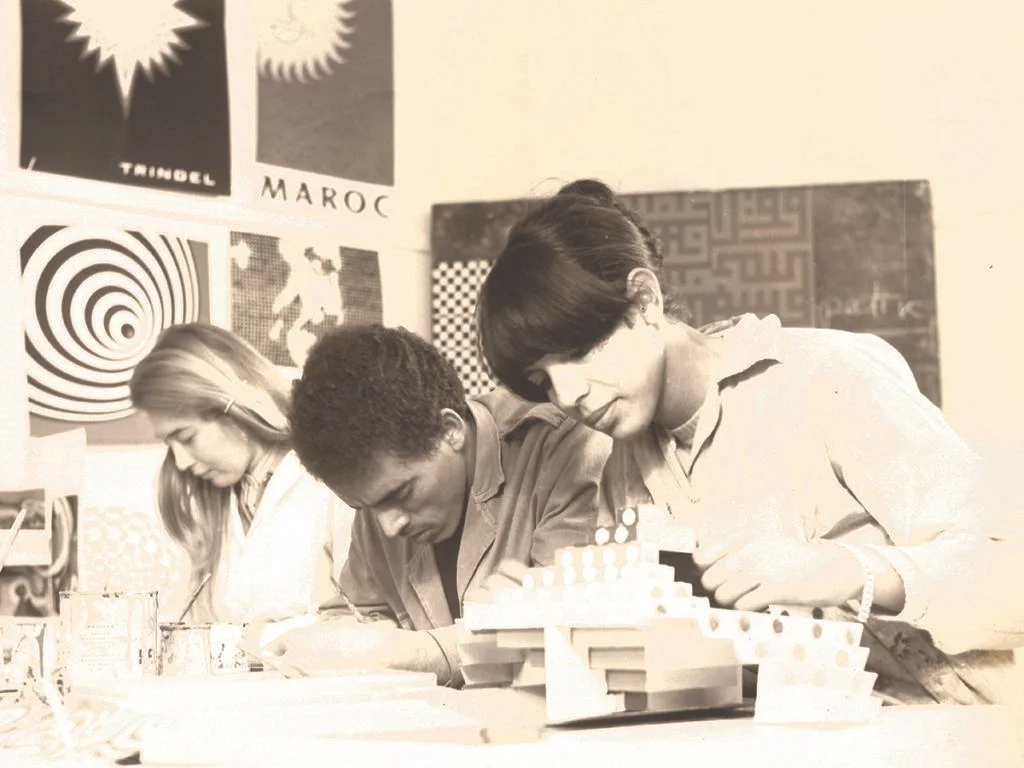

Mohamed Melehi (in chair) at the Casablanca Art School with a group of teachers (including Mohamed Chabâa and Farid Belkahia) and students (among them, on the far right, Malika Agueznay). Photograph by Toni Maraini. Photo: Courtesy of Malika Agueznay

Pre- to Post-Colonial Art Revolution

Morocco’s independence from French and Spanish colonial rule in 1956 sparked a deliberate and powerful decolonization movement: this was a cultural revolution in action, one which sought to rediscover, redefine and reimagine what post-colonial Morocco would look like. The Casablanca Art School (CAS) was one focal point for this revolution where art, its production, its enjoyment, the access to it and teaching of it became a vehicle for social reimagination. The CAS thus became a space in which social and artistic aspirations were able to crystallize.

The innovative and revolutionary teaching staff, led by Farid Belkahia, broke away from Western academic traditions and epistemologies. Continuing what Belkahia’s predecessor, Maurica Arama (the first Moroccan director of the school) had started, this avant-garde group “radically questioned cosmopolitan abstraction and art pedagogy within the context of colonial powers and influences” thus creating a rupture and space for a new multi-disciplinary pedagogy which centered Moroccan artistic and cultural heritage. Their practice and approach was inspired by the Bauhaus Manifesto. Within this framework, the CAS group began to "rethink the relationship between arts, crafts, design and architecture within a local context." They understood art not just as a visual or aesthetic practice, but a process that could ignite social transformation. Farid Belkahia took on the mantle as the school’s director with a push to democratize the curriculum: he allowed Moroccan and women students to enroll, “revolutionize[d] the school’s curriculum and structure to synthesize regional artisanal skills with modern applications”, and started to break away from the school’s colonial origins.

Belkahia brought together a “radical faculty”, including Mohamed Melehi, Mohamed Chabaa, Toni Maraini and Bert Flint, all of whom “rejected academic easel painting and orientalist figuration, embracing instead the interdisciplinary approach of the Bauhaus.” Together, they began to cultivate a new understanding of art: its conception and its place in society, and forged a new, Moroccan modernism that was rooted in local visual culture. They were at the forefront of “reimagining what modern art in post colonial Morocco could be.”

“Tradition is the future.”

Abandoning the Western artistic canon, the disruptive curriculum instead taught students to re-appreciate and re-engage with the traditional arts of Morocco from different vantage points — whether that was artistic practice, theory or anthropology. A diverse and interdisciplinary program of study that included painting, sculpture, graphic design, typography and more “encouraged students to look beyond Western art history and develop interest in local artistic production and artisanry.”

Présence plastique, Jemaa El-Fna Square Manifesto exhibition, (including Ataallah, Belkahia, Hafid, Hamidi, Chabaa, Melehi), Marrakech, May 1969, Toni Maraini Archives. Photo credit: Lenbachhaus

Democratizing Art

Présence Plastique, Jemaa al-Fna Square

While the colonial era had kept fine art firmly behind closed doors, the Casablanca movement flung the gates open. Belkahia, Melehi and Chabâa – who came to be known as the Casablanca Trio – brought their art outside the traditional state-organized “salons” which “sidelined and undermined the agency of Moroccan artists” to public spaces: first in a joint exhibition in a hall at the Mohammed V Theatre Rabat in 1966 and then in Marrakech in 1969.

Presence Plastique, an outdoor manifesto exhibition staged in Marrakech’s Jemaa al-Fna Square, pronounced that modern art was to be a non-elitist part of everyday life – something to be enjoyed by everyone and anyone. By bringing their abstract and modern artworks to the city’s public squares, “they engaged people from all walks of life and every social class away from the rarefied environment of galleries and salons.” Writing in Souffles (a literary review that was launched by poet Abdellatif Laâbi in 1966), the collective reiterated the purpose behind this “living art demonstration” to bring art “outside the closed circle of galleries, of salons which this audience has never entered.” They wanted to embed art as part of the public’s rhythm of life and daily space and to “awaken [their] interest, curiosity and critical spirit.”

Présence Plastique, Jemaa el-Fna square, Marrakech (May 1969). © M. Melehi archives/estate. Photo: M. Melehi.

The Asilah Festival

The street exhibitions and outdoor murals of the Asilah Festival (The Cultural Moussem of Asilah), co-founded by politician Mohamed Benaissa and Mohamed Melehi in 1978, also “br[ought] contemporary art directly to the community.” Ongoing to this day, the festival has “significantly shaped the cultural context for arts to interact with public spaces,” and has had an indelible influence on the urban regeneration and conservation of the town itself.

Souffles-Anfas

Concurrently, Souffles brought together much of the same decolonial and aesthetic thinking. It “became a conduit for a new generation of writers, artists, and intellectuals to stage a revolution against imperialist and colonial culture domination.” It was all at once a “node, medium and interface in the intellectual, political and artistic production of a nascent Moroccan postcolonial subjectivity.” It also provided a critical vehicle for cultural renewal adjacent to and, in many ways, part of the CAS movement. Melehi volunteered as art director and the journal welcomed contributions from many of the CAS artists. The journal was banned in 1972 and Laâbi was imprisoned alongside Chabâa.

The Casablanca Art School’s Legacy

The Casablanca Art School forged a new art for Morocco grown from Afro-Amazigh heritage, and in doing so it revolutionized both Morocco’s cultural and social spheres. Perhaps most significant of all was the movement’s efforts to democratize art, create a new aesthetic lexicon that was profoundly Moroccan, and carve out a type of modernism that was intrinsically tied to its local context.

Key Figures of The Casablanca Art School

In this section, we delve into the lives, experiences and individual artistic practices of some of the Casablanca Art School’s key figures and names that are often mentioned in relation to them.

Farid Belkahia, “Aube (Dawn),” 1983. Pigment on vellum, 11 3/4 x 14 1/8 in. Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah, UAE

Farid Belkahia (1934-2014)

A driving force behind the Moroccan modern art movement, Belkahia’s contributions to Morocco’s art scene reverberated across the region, helping to usher in a new artistic era far beyond his hometown of Marrakech.

Born in 1934, Belkahia grew up surrounded by art and artists, including Polish artists Antoine and Olek Teslar and French artist Jeannine Guillou. Belkahia went on to study at Paris’ École des Beaux-arts between 1955 and 1959 before returning to Morocco to teach art and eventually take on the role of director at the Casablanca Art School.

Belkahia’s early art exposure and training was oriented towards Western schools of thought and he was “both inspired and influenced by the minimalist and modernist aesthetics from the West.” But his practice eventually shifted to center a Moroccan aesthetic: one which sought to “compete against Western influence with the definition of a specifically Moroccan modernity.”

This was particularly pertinent in the context of a newly independent, post-colonial Morocco. In this vein, Belkahia started to incorporate traditional techniques, mediums, materials and processes into his artistic practice. For instance, he started painting with organic pigments on leather and using materials such as copper and ram’s skin — thus adopting and reinvigorating a traditional method but with an emphatically contemporary approach.

Mohamed Melehi, Untitled (1983). Cellulose paint on board. 150 x 200 cm. © Mohamed Melehi Estate.

Mohamed Melehi (1936-2020)

Melehi was also at the core of the cultural and artistic revolution sparked by the Casablanca Art School. Like his contemporaries, he contributed immensely to redefining and reimagining what art might look like in post-colonial Morocco with work that “resists the East/West divide resulting in a dialogue between Moroccan traditional and popular craft, whilst also connecting to the Hard Edge painters of the 1960s.”

Born in Asilah in 1936, Melehi studied at the Ecole des Beaux-arts in Tetouan before traveling to Spain and then Italy to further his artistic education. While studying sculpture in the Accademia di Belle Arti in Rome between 1957 and 1961, he met Topazia Alliata – the owner of the Trastevere gallery and his future mother-in-law. Alliata would go on to introduce him to key players on the Roman art scene namely: Alberto Burri, Guiseppe Capogrossi and Jannis Kounellis.

Melehi was influenced greatly by the way these artists used found materials, which inspired him to incorporate materials and techniques that echoed Amazigh heritage and culture. It was also during this period that he discovered the work of American abstract expressionist painters Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Robert Rauschenberg.

From Rome, Melehi moved to the United States in 1962, first to the Minneapolis Institute of Art where he took up a position teaching assistant, then to New York on a Rockefeller Scholarship to study Art History at Columbia University. During his time in the city, he mingled with key players associated with the Leo Castelli gallery such as Hard Edge artist Frank Stella. He went on to participate in the Hard Edge and Geometric Painting group exhibition at MOMA in 1963, which cemented the “maturation of the wave, his emblematic motif, throughout the 1970s and 1980s.” Concurrently, a noticeable shift occurred in his work: a transition away from a dark, neutral palette towards the vibrant colorscapes that came to define his work.

He returned to Morocco in 1964 where he joined the Casablanca School of Art as a professor teaching painting, sculpture, collage and photography. Melehi’s contributions to Morocco’s artistic and cultural scene didn’t stop at the school: between 1966 and 1969, he volunteered as the art director of socio-political literary magazine, Souffles-Anfas, launched a literary review entitled Integral with his wife in 1971, and opened his own graphic design studio called SHOOF in 1974.

In 1978, Melehi co-founded an annual arts festival, The Cultural Moussem Asilah, in his hometown, with Moroccan poet, writer and journalist Mohamed Benaissa. He also took up positions in the government: acting as arts director at the Culture Ministry between 1985 and 1992 and cultural consultant to the ministry of foreign affairs and cooperation between 1999 to 2002.

Mohamed Melehi (left) at his studio in Casablanca with Mohamed Chabâa. Photo: © M. Melehi archives/estate

Mohamed Chabâa, Composition. 1967. Société Générale de Maroc Collection

Mohamed Chabaa (1935-2013)

A painter, sculptor, muralist and graphic designer with a great passion and interest for architecture, Chabaa “characterized his art as a ‘social practice’, which materializes a sort of visual education for the community.” He was born in Tangiers in 1935 and studied at the School of Fine Arts of Tetouan. After graduating in 1955, he took a job working for the Ministry of Youth and Sport in the architecture department. Later, he attended the Accademia di Belle Arti in Rome to study interior design. There he conceptualized the theory of the 3A which stood for Art, Architecture, and “Artisanat” (referring to arts and crafts): a notion that grew out of his exposure to Bauhaus philosophy and Italian Renaissance works.

Under this construct, one was to be “simultaneously an artist, an artisan and an architect” – echoing the key tenets of the Bauhaus movement. He returned to Morocco in 1964 and joined the School of Fine Arts of Casablanca in 1966. Two years later he founded Studio 400, a design and interior design workshop, through which he sought to put his 3A theory into practice.

Toni Maraini teaching African art history at the Casablanca Art School, 1964-65. Photo: M. Melehi. © M. Melehi archives/estate.

Toni Maraini

Maraini is a poet, writer, art historian and anthropologist – and the daughter of Topazia Alliata and second wife of Mohamed Melehi. She was invited by Farid Belkahia to establish a modern art history course at the CAS and taught art theory and practice there. She was a driving force within the Casablanca movement acting as “principal theoretician of the group…[writing] the manifestoes, critical texts and catalogs for Belkahia, Chabaa, and Melehi…” She co-founded Integral magazine in 1971 with her husband.

ondation Jardin Majorelle, photo: Mouad Fahmi.

Bert Flint

Bert Flint was a Dutch anthropologist and researcher of popular arts and rural tradition. He joined CAS to teach African and Amazigh popular art as well as visual anthropology in 1965, and was an integral part of the wider Casablanca school movement. He had a personal collection of Moroccan artifacts and art and “was brought in as part of a mission to revalorize Moroccan craft.”

Mohamed Ataallah, Composition, Tanger, c1965. © Mohamed Ataallah Estate. Courtesy of private collection, Marrakesh.

Mohamed (Romain) Ataallah

Born in Ksar el-Kebir in 1939, Ataallah also studied at the National Institute of Fine Arts in Tetouan, and pursued further studies in Seville and then Rome, before returning to Morocco in 1963 to participate in archeological excavations near Tangiers. He joined the Casablanca School in 1968 and remained there until 1972, when he moved to France to teach at the School of Fine Arts in Caen.

Mustapha Hafid, Voyage cosmique (Cosmic journey), 1972. Mixed media, 159.5 x 120.5 cm. © Collection of the artist.

Mustapha Hafid

Affiliated with the CAS first as a student and later as a professor, Mustapha Hafid’s artistic life was very much tied to the school. After graduating from CAS, Hafid moved to Warsaw to study at the city’s Academy of Fine Arts. After achieving a Master of Arts, he returned to Casablanca to teach. His artistic practice brings organic and synthetic mediums together. His wife, Anna Draus-Hafid, opened a weaving studio at the Casablanca Art School in 1974. He acted as temporary director of the school in 1980 and in 1985.

Mohamad Hamidi, Untitled 1969

Mohamed Hamidi

Hamidi was born in Casablanca in 1941 and also started his journey as a student at the CAS and then later as a professor. He studied at the Ecole des Beaux-arts in Casablanca and then moved to France where he enrolled at the Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux-arts. He’s known for his works that include “Africanist and erotic style of compositions, combining sexual elements with popular arts and crafts patterns.” He was involved with the search for a specifically Moroccan modern aesthetic. As a member of the CAS teaching staff, he “participated in the development of methodology to teach the history of Moroccan craftsmanship, from carpet and jewelry design to ceramics.” He was also a founder of the Association Marocaine des Arts Plastiques (Moroccan Association of Plastic Arts) which sought to forge connections between Moroccan artists and other artists from across the region.

Malika Agueznay. Symbole féminin. 1968. Image courtesy of Malika Agueznay

Malika Agueznay

Credited as one of the first Moroccan women to experiment with abstraction, Malika Agueznay was also at the heart of cultivating a modern Moroccan artistic lexicon. Agueznay joined the Casablanca School of Fine Arts in 1966 and is considered (by MoMA at least) “the only major woman artist linked to the institution during this pivotal time.”

Her work and practice emphatically centers the female experience and perspective and it was thus that she was able to “forge a space for herself within a predominantly masculine environment.” The motif that is so central and emblematic to her work is seaweed, which has been “relat[ed] to the curves of the female body or to the multiplication of cells as a symbol of life…”